Abstract

This paper critiques India’s Competition Act, 2002, and its implementation, arguing that the act reflects an inherent bias against large enterprises. The paper examines the Competition Commission of India’s inconsistent approach in abuse of dominance cases, oscillating between form-based and effects-based analyses. It highlights challenges in defining relevant markets, establishing dominance, and calculating penalties on the basis of inconsistent standards. It also explores the complexities of regulating digital markets. The author advocates for a more nuanced, evidence-based approach that does not penalize scale and considers actual harm to competition and consumers.

Introduction

Is Uber being anticompetitive if it offers substantial discounts? Are cable TV operators and channel broadcasters even competitors in the same market? Indian regulators seem to think so, driven by an inherent anti–big business bias that often leads to absurd conclusions and interventions. The governing law on market competition in India, the Competition Act, 2002,[1] reinforces this bias in its very design, often equating size with wrongdoing.

This bias has deep roots in India’s economic history. The legacy of the License Permit Raj, characterized by high entry barriers and protectionism, created a few dominant and anticompetitive domestic enterprises. Instead of fixing those perverse policies directly, India relied on its then-existing competition policy, the Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices (MRTP) Act, 1969, to curb big businesses, as they were uncontestable because of permit requirements.

Market liberalization since 1991 removed many such entry barriers, fostering contestability and innovation. The 2002 act was meant to move away from the MRTP Act’s focus on curbing big businesses and instead foster competitiveness and promote gains from market efficiencies, ultimately benefiting consumers. However, the anti–big business bias persists in its implementation. The new market regulator, the Competition Commission of India (CCI), and the appellate judicial framework continue to follow the outdated playbook of the MRTP Act, remaining suspicious of large and globally competitive firms.

Competition policy worldwide, however, has moved beyond such bias, recognizing that contestability is the true measure of market health and that the process of competition is inherently destructive, with rivals vying for customers, market share, and innovation. While some firms fail, others succeed, but the success of a few top players—achieved through superior products and services that benefit consumers—does not necessarily harm competition.

Contemporary competition policies recognize this aspect of markets and aim to preserve the competitive process rather than protect or punish specific competitors or incumbents. These policies craft proportionate remedies for anticompetitive actions that harm consumers. Such remedies let large firms achieve economies of scale driven by efficiency and innovation, benefiting consumers with increased output, lower prices, and enhanced choice.

Some have argued that the goal to protect the competitive process has rhetorical appeal but does not offer enough guidance for the concerned regulator.[2] Relying on a concrete standard—such as the welfare of the end consumer—provides a more concrete basis for assessing whether a firm’s conduct is harmful. Per this standard,[3] regulators can evaluate the implications of a firm’s actions by examining their impact on the output of goods and services and the corresponding change in prices.

This consumer welfare-focused approach contrasts with India’s anti–big business bias. I argue in this paper that big business is, by default, suspect in India. The 2002 act presumes that specific actions by dominant firms constitute abuse of dominance without considering efficiency gains and consumer benefits or requiring evidence of actual harm to competition or consumers. CCI oscillates between making such assumptions and occasionally assessing the real effects of a dominant firm’s actions on the market and consumers, thereby creating legal uncertainty. Furthermore, the law’s penalty standards are also inconsistent and disproportionately affect global firms. CCI’s decisions particularly disadvantage big tech companies by failing to consider the unique dynamics of digital markets. What India needs instead is a more nuanced, evidence-based approach to competition law that is sensitive to the realities of its economy and does not punish scale.

I. Big Is Still Bad

Despite market liberalization and the enactment of the 2002 act, the anti–big attitude persists in the Indian competition regime. The Uber case is a prime example of this bias.[4] Two years after entering the Indian market in 2013, Uber faced allegations of curbing competition in the radio-cabs market. Meru Cabs, a domestic competitor, accused Uber of abusing its dominant position in Delhi–National Capital Region by offering prices below cost and incentivizing drivers to eliminate competition. Although CCI initially dismissed the complaint, the appellate tribunal ordered an investigation questioning whether Uber’s discounts indicated “phenomenal efficiency improvements” or anticompetitive behavior, without an assessment of market dynamics and consumer welfare.[5]

In the appeal, the Supreme Court concurred and ordered an investigation, noting that Uber’s incentive strategy for a fleet owner with four cars and nine drivers—which resulted in a loss of Rs 204 per ride in June 2015—was economically illogical, and thus, prima facie, aimed at eliminating competition.[6] It never evaluated, even cursorily, Uber’s market dominance or its impact on consumers, nor did it consider that drivers use multiple driving applications, and Uber does not lock in the physical or human capital.

Eventually, upon reinvestigation, CCI concluded that Uber was not dominant, and its practices were not anticompetitive. On the contrary, CCI found that the radio-cab services market was, in fact, competitive.[7] It took six years for the Indian regulatory system to conclude the obvious. As a result, from 2015 to 2021, the world’s largest ridesharing company diverted resources to defend its business model across different Indian forums, hampering its growth and expansion. No one considered how many additional drivers could have been employed to serve populations without access to cars.

The broader trend of opposition to bigness is more apparent in Section 28 of the 2002 act. The provision empowers CCI to divide an enterprise to ensure that it does not abuse its dominant position, without requiring an actual instance of abuse of such a position and consequent harm. Though Section 28 has never been imposed, a provision enabling such unchecked intervention should not be on the books.

This issue becomes particularly relevant when one considers the current landscape of Indian conglomerates and recent scholarship exploring the idea of breaking up large conglomerate groups in India.[8] The big five conglomerates in India—Reliance (Mukesh Ambani) Group, Tata Group, Aditya Birla Group, Adani Group, and Bharti Telecom—now have a finger in every pie, from metals and minerals to retail and telecommunications. They command a hefty slice of the assets in more than 40 major sectors (NIC-two-digit[9] nonfinancial sectors). Their share in total assets of these sectors grew from 10 percent in 1991 to 18 percent in 2021. And the share of the next five biggest groups shrank from 18 percent in 1992 to less than 9 percent in 2021. Some see this trend as a sign of market power concentration, suggesting it could impact competition, prices, and India’s overall economic health.[10] But is it inherently wrong for a company to be big, especially if its growth is driven by efficiencies and innovation? Does size pose a threat to market competition?

Section 28 echoes the US trustbuster strategy in the 1900s of breaking up large companies, or “trusts,” that had monopolistic control over specific industries such as oil and railroads.[11] However, in the Indian economy, forcibly splitting conglomerate groups might set a disturbing precedent, potentially dissuading both domestic and foreign investors. It is akin to fixing a watch with a sledgehammer—you might end up with more pieces, but you will likely damage the underlying mechanism.

II. Abuse of Dominance Is Per Se

Under the 2002 act, CCI has broad powers to investigate, either suo moto or on the basis of complaints, and to penalize anticompetitive practices,[12] such as collusion among cartels to raise prices. When it comes to large enterprises, CCI can investigate and penalize such companies if they are found to be abusing their dominant position in the market. It is not dominance but abuse of dominance that is penalized under Section 4 of the 2002 act. However, Section 4 condemns certain practices by dominant firms as abusive per se,[13] without considering whether those practices actually have an adverse effect on competition and are detrimental to consumers.

Consider the cable TV market in the state of Punjab and the union territory of Chandigarh.[14] A group of multisystem operators, or cable operators, contracted with different broadcasters to provide TV channels to 85 percent of cable TV subscribers in the state. A new news broadcaster, X, entered the market and signed an agreement with the cable operators to carry its channel on their network. However, a few months later, the cable operators abruptly terminated the contract because of low ratings, effectively pulling X’s channel off the air.

X filed a complaint with CCI against the cable operators for abusing their dominance in the market. CCI defined the relevant market as the market for cable TV services that platform news channels, distinguishing that market from other platforms, such as direct-to-home services, on the basis of different pricing and quality of services. CCI concluded that the cable operators did indeed have a dominant position, given the group’s market share of 85 percent[15] and given that “they were able to operate independently of competitive forces prevailing in the market.”[16]

This kind of investigation is representative of CCI’s assessment of dominance. When faced with a complaint of abuse of a dominant position, CCI has to determine (a) the contours of the markets in which the violating firm is operating and selling its wares[17] (relevant product and geographic markets) and then (b) whether it is dominant in the identified markets.[18]

However, why did CCI consider only cable TV services that platform news channels? Why not consider all media platforms, including digital platforms such as YouTube, that feature news channels? What is the bright line rule when determining the relevant market?

Defining relevant markets

There are inherent challenges in determining relevant markets. Overly broad definitions of the relevant market risk that false negatives, such as anticompetitive conduct in distinct submarkets, may go undetected. Excessively narrow definitions can lead to false positives, as firms may be incorrectly deemed dominant in artificially segmented markets.

Consider the smartphone, a product so ubiquitous and essential in modern life that the market for it is intensely competitive across different price segments. If CCI defined the relevant market as all smartphones in India, even a major manufacturer such as Samsung might not appear dominant, given the fierce competition and diverse consumer choices. However, narrowing the focus can dramatically alter this assessment. If the market were defined as smartphones with ISOCELL camera sensors, Samsung’s position would suddenly seem more dominant, as it both produces these sensors and, along with only a handful of other manufacturers, uses them in its phones. Narrowing further to smartphones with specific features, such as Galaxy AI, would shrink the competitive field even more, as this technology is exclusive to certain Samsung models. This progression illustrates how, despite the product’s ubiquity and the market’s competitiveness, CCI’s definition of the relevant market can suddenly transform a company from one competitor among many to a dominant firm. Such malleability in market definition highlights the potential for regulatory overreach in a dynamic and innovative sector.

Grasim Industries Limited, India’s leading manufacturer and exporter of viscose staple fiber (a type of semi-synthetic fiber), sells the material to various spinners across the country, who use it to produce yarn. Several small spinners filed a complaint with CCI alleging that Grasim charges discriminatory prices for viscose by selling at different rates to domestic spinners, exporting spinners, and foreign spinners and that it imposes unfair conditions such as requiring the spinners to provide detailed data on their viscose consumption and yarn production as a condition for receiving discounts on purchases of viscose.[19] In another instance, a yarn spinner accused Grasim of denying market access when it refused to give the spinner discounts.[20]

CCI defined the relevant market as the “market for the supply of viscose staple fiber to spinners in India.” On the basis of that definition, CCI concluded that Grasim has a dominant position because it is the largest domestic producer of viscose and because imports account for only a small portion of the market. CCI did not adequately consider the possibility that other types of fibers could serve as substitutes for viscose from the perspective of the spinners (demand-side substitutability). By focusing solely on the technical differences between viscose and other fibers, CCI deemed viscose to be nonsubstitutable. CCI also did not examine whether producers of other fibers could potentially switch to producing viscose in response to a change in market conditions (supply-side substitutability), such as a small but significant nontransitory increase in price.[21] By defining the market so narrowly, CCI overstated Grasim’s market power. A broader market definition, including other fiber types, might have shown Grasim’s position to be less dominant.

Defining the market at a given point in time also risks ignoring market dynamics. For instance, in the case of the cable operators, CCI did not foresee the growing competitive constraints from alternative platforms, including the possibility that news channels would stream online and the extent of internet and mobile usage by the time the matter was settled by the Supreme Court. Therefore, it narrowly defined the market, which established the dominance of the cable operators at that point in time.

These are the perils of ad hoc market definitions untethered from sound economic principles. The implications are profound: a narrow market definition can erroneously signal dominance and invite unwarranted regulatory actions, while an overly broad definition might miss nuanced anticompetitive behaviors, thus leaving consumers unprotected.

Abuse of dominance is assessed formalistically

Once a firm is deemed dominant, a domino effect is set off. If it has been alleged that the firm deemed dominant has engaged in any of the activities listed under Section 4 of the 2002 act, then CCI will penalize the firm.

For example, a courier company in the union territory of Chandigarh could be deemed dominant, given that for such a small coverage area, there could be only one, or at best two, of such companies. The company could charge significantly higher fees to commercial clients compared with household customers or offer preferential rates to select large-volume customers while overcharging others,[22] or it could provide conditional services, such as agreeing to handle time-sensitive deliveries only if customers sign up for the company’s bulk-shipping services or offering premium tracking exclusively to those who commit to long-term contracts.[23] To expand its business, the company could enter neighboring states such as Punjab or Haryana with really low delivery fees and could cause customers to switch their service to the company, possibly eliminating local courier companies.[24] The company could also expand its business by entering the market of same-day pickup and drop-off delivery services, thus competing with new digital platforms. Because the company already has established resources, infrastructure, and market power in the traditional courier service, it could capitalize on those advantages. As a result, it could offer same-day services at prices that new entrants couldn’t match, bundle same-day deliveries with its regular services at discounted rates, or use its existing customer base to rapidly scale its new service, effectively crowding out the new digital platforms that lack those preexisting advantages.[25] All these activities are punishable under Section 4 because the company is deemed dominant.

This formalistic approach in the law, however, can lead to overenforcment. For example, the Chandigarh courier company’s practices that are not actually exclusionary could still be penalized if they fall within the listed categories under Section 4(2). Interestingly, there’s an inconsistency in the law’s application: The courier company may justify its differential pricing between commercial and household customers or its low-price entry into neighboring states if such strategies are meant for efficiency-enhancing, procompetitive discrimination.[26] However, if the company insists on supplemental agreements (such as bundling time-sensitive deliveries with bulk shipping) or leverages its position to dominate the same-day delivery market, the law doesn’t provide exemptions on procompetitive grounds.

This raises an important question: If none of these practices hurt the consumer in terms of rates, choice, and quality of service, should the Chandigarh courier company be punished for providing the best services? For example, if the company’s entry into the same-day delivery market actually improves service quality and lowers prices for consumers despite crowding out some digital platforms, are the company’s activities truly harmful? Shouldn’t CCI evaluate whether these activities ultimately reduce choices and raise prices for consumers in Chandigarh and the surrounding regions or whether they are actually benefiting consumers while incidentally affecting competitors? This approach would focus on discovering the actual market effects rather than simply applying a checklist of prohibited behaviors. However, CCI has not applied this approach consistently, leading to more uncertainty.

III. Oscillating between Form-Based and Effects-Based Assessment of a Firm’s Conduct

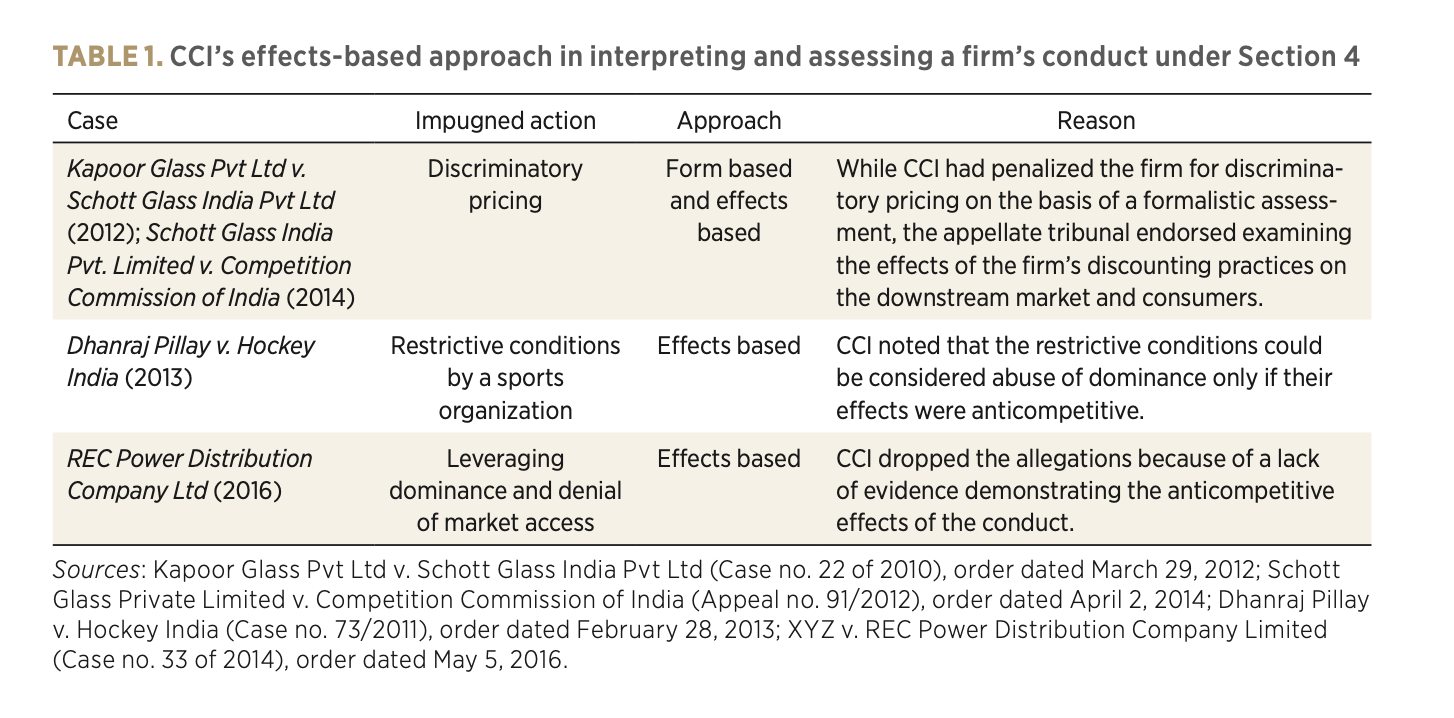

Despite the language of the statute, which mandates a formalistic assessment of a firm’s conduct, CCI has not consistently adhered to a strict per se approach in decisional practice. It has oscillated between a form-based approach that presumes harm without evidence and an effects-based assessment that considers the actual impact on competition and consumers.[27]

In the Grasim Industries cases, CCI penalized the firm for practicing discriminatory pricing and for imposing unfair conditions but did not analyze the effects on downstream yarn spinners or garment consumers. Suppose Grasim’s price discrimination or denial of discounts did not lead to higher prices, reduced output, or exclusion of competitors in the downstream market. What exactly is the meaning or outcome of abuse of dominance in that instance? Moreover, in the other case, the firm that was denied a discount was already in a commercial dispute with Grasim. CCI’s form-based approach in the Grasim cases demonstrates the overreach of the regulator because it presumed certain actions by dominant firms as abuse of dominance without assessing their actual effects. Such an approach risks overenforcement and unwarranted punishment of competitively neutral or procompetitive actions.

In the case of the complaint against the cable operators in Punjab, they actually terminated the contract of the news channel X, which they had never done with any other broadcaster. X, therefore, alleged denial of market access, one of the grounds for legal action under Section 4.[28] CCI penalized the cable operators for abusing their dominant position since the law does not stipulate that CCI must check whether the termination had downstream consequences for consumer welfare. For example, by canceling the contract with X, did the cable operators hurt consumer welfare when seven other news channels were already platformed? CCI never asked that question.

CCI’s approach was formalistic: since the cable operators had a dominant market share, the termination of X’s contract was deemed abuse, and the cable operators were slapped with a penalty. The appellate tribunal set aside this order, reasoning that the cable operators were not even in competition with the news channel X, so there could be no infringement, and the question of assessing dominance and its abuse did not arise.[29]

On appeal, however, the Supreme Court overturned the appellate tribunal’s order. It held that once a dominant position is demonstrated, whether the cable operators compete with the broadcaster is irrelevant to Section 4. In a way, the court was taking the form-based approach too far and to absurd conclusions. However, the apex court accepted the cable operators’ reason for dropping the channel because of low ratings and set aside the monetary penalty of Rs 8 crore, or Rs 80 million.[30] If Section 4 had required an assessment of the effects of the firm’s conduct from the start, this protracted litigation and its awkward outcome could have been avoided.[31]

In some cases, CCI has assessed the effects of the firm’s conduct, and in the absence of evidence showing actual harm, it has ruled in favor of the firms (see table 1). For example, an informant brought a case against mobile phone manufacturer Apple and service providers Vodafone and Airtel for their exclusive tying arrangements. CCI identified their relevant markets by looking at factors such as product substitutability, technological differences, and consumer preferences, rejecting the informant’s narrow definition of the market as consisting only of Apple iPhones.[32] When assessing dominance, CCI considered factors outlined in Section 19(4) of the 2002 act, such as market share, entry barriers, and countervailing buyer power. The commission found that none of the firms (Apple, Airtel, or Vodafone) were individually dominant in their respective relevant markets of smartphones and service providers, respectively.

Importantly, CCI recognized that the mere presence of dominance is not sufficient to establish abuse of dominance or anticompetitive conduct. The regulator analyzed the alleged tying arrangement between Apple and the service providers, considering its potential effects on the market, such as the impact on competitors. CCI found no evidence of actual harm and noted the potential procompetitive effects of the arrangement.

In a recent order,[33] the appellate tribunal is perceived to have settled the debate as it held that Section 4 requires an analysis of the effects of a dominant firm’s actions to establish abuse of dominance. The tribunal also relied on the suggestion of the Competition Law Review Committee that no amendment to Section 4 is necessary as the decisional practice has evolved to incorporate effects-based analysis.[34] However, this practice has been inconsistent and, until upheld by the Supreme Court, the order does not conclusively resolve the issue that Section 4, as currently drafted, warrants a formalistic assessment of abuse of dominance. The issue of CCI’s inconsistent decisional practice was flagged in the dissent note of a member of the Competition Law Review Committee. The regulator, CCI, in fact, argues for a formalistic assessment of abuse of dominance in appeals against the orders of the appellate tribunal where the effects of the firm’s conduct have instead been assessed.[35]

Amending Section 4 by incorporating an assessment of the effects of a dominant firm’s conduct into the letter of the law is therefore necessary. This amendment would ensure that CCI focuses on practices that harm competition and would provide clarity to businesses regarding what constitutes an abuse of dominance.

Furthermore, amending Section 4 to incorporate an effects-based assessment will address the inconsistency between Sections 4 and 32 of the 2002 act. Section 32 extends the jurisdiction of CCI to cover acts outside India that affect competition in India. This section requires an effects-based assessment of a foreign-based enterprise’s abuse of its dominant position. In contrast, as discussed earlier, conduct occurring within India is assessed under Section 4 without an effects-based approach. This disparity in regulatory approach is not a matter of favoring certain firms over others but rather a policy inconsistency that results in two distinct types of assessment for firms’ conduct, with no sound rationale for such a divergence. This inconsistency in approach undermines the coherence and equitable application of competition law in India, regardless of where the conduct originates.

IV. Oscillating between Different Standards for Calculating Penalties

After establishing dominance and abuse of dominance, regulators impose penalties to deter anticompetitive behavior and promote regulatory compliance. The primary objectives of penalties in competition law are to punish the violator, deter future violations, and signal the seriousness of the offense to the broader business community.

Antitrust enforcement mechanisms converge on the principles that any remedy or penalty imposed must “be clear and precise so that the undertaking may know without ambiguity its rights and obligations and may take steps accordingly” and that “tailoring the remedy to the harm allows competition authorities to require the least intrusive remedy without compromising effectiveness.”[36] The principle of proportionality underpins these mechanisms. This principle ensures that penalties are proportionate to the gravity of the infringement and the harm caused to competition and consumers while also preventing the infringing party from suffering punishment disproportionate to the conduct itself. It is crucial to consider whether the firm will have the opportunity to course-correct its behavior or whether the compliance burden of heavy penalties might force it to shut down. Additionally, the standards for imposing penalties should be consistent across all firms to ensure fairness and predictability in the regulatory environment.

Many jurisdictions,[37] including the European Union (EU) and the United Kingdom, impose financial penalties by using turnover as the basis for calculating penalties. The rationale behind using turnover is that it serves as a proxy for the size and economic power of the enterprise and assumes that a penalty based on the firm’s turnover will deter its anticompetitive conduct in the market. The only saving grace is that there is a method to this seeming madness: these jurisdictions have clear guidelines and a systematic approach to calculating the penalty.

In the EU, the penalty is capped at 10 percent of total turnover. However, the EU follows a guided two-step method, which involves determining the base penalty on the basis of the value of relevant sales and making appropriate adjustments for aggravating or mitigating factors. Therefore, it is effectively penalizing enterprises on the basis of the relevant turnover.[38]

In the United Kingdom[39] and Singapore,[40] while the specific methods vary, the regulatory agencies consider the relevant turnover of the undertaking, which refers to the turnover generated from the goods or services directly or indirectly related to the infringement. This method ensures that the penalty is proportionate to the scale and impact of the anticompetitive conduct. Focusing on relevant turnover provides a more accurate reflection of the economic significance of the infringement and its potential harm to competition and consumers, compared to using the total or worldwide turnover of the undertaking.

Arbitrary and vague imposition

In the Indian context, Section 27 of the 2002 act empowers CCI to impose penalties on enterprises that abuse their dominant position. The act prescribes that the penalty can be up to 10 percent of the average turnover for the past three financial years. Turnover under the 2002 act includes the value of sales of goods and services.[41] However, the act does not provide specific guidelines on the calculation or assessment of turnover, leaving it to be determined by further regulations. Until 2024, such regulations were never issued. As a result, Indian regulators have convoluted the definition of turnover altogether and changed its meaning three times in the 15 years since the provision has been in effect.[42]

Three times wayward

When the 2002 act came into effect, CCI deemed turnover to mean total turnover of the enterprise. Per this interpretation, CCI looked at the total value of all goods or services provided by the enterprise, regardless of whether they were related to the abuse of dominance. Though, in a way, this approach imitates the EU’s standard of using total turnover, CCI did not adopt the scaling or variation in the calculating process using the value of relevant sales as the base. It just levied penalties that were based on the value of the total sales of a violating firm, regardless of whether such sales had any nexus with the abuse of dominance.

After several varied approaches, the Supreme Court, in the Excel Crop Care case in 2017,[43] interpreted turnover to mean relevant turnover—the turnover of the products or services that are the subject matter of the infringement. Although the case primarily dealt with anticompetitive agreements, the principle of relevant turnover was also applied to abuse of dominance cases.

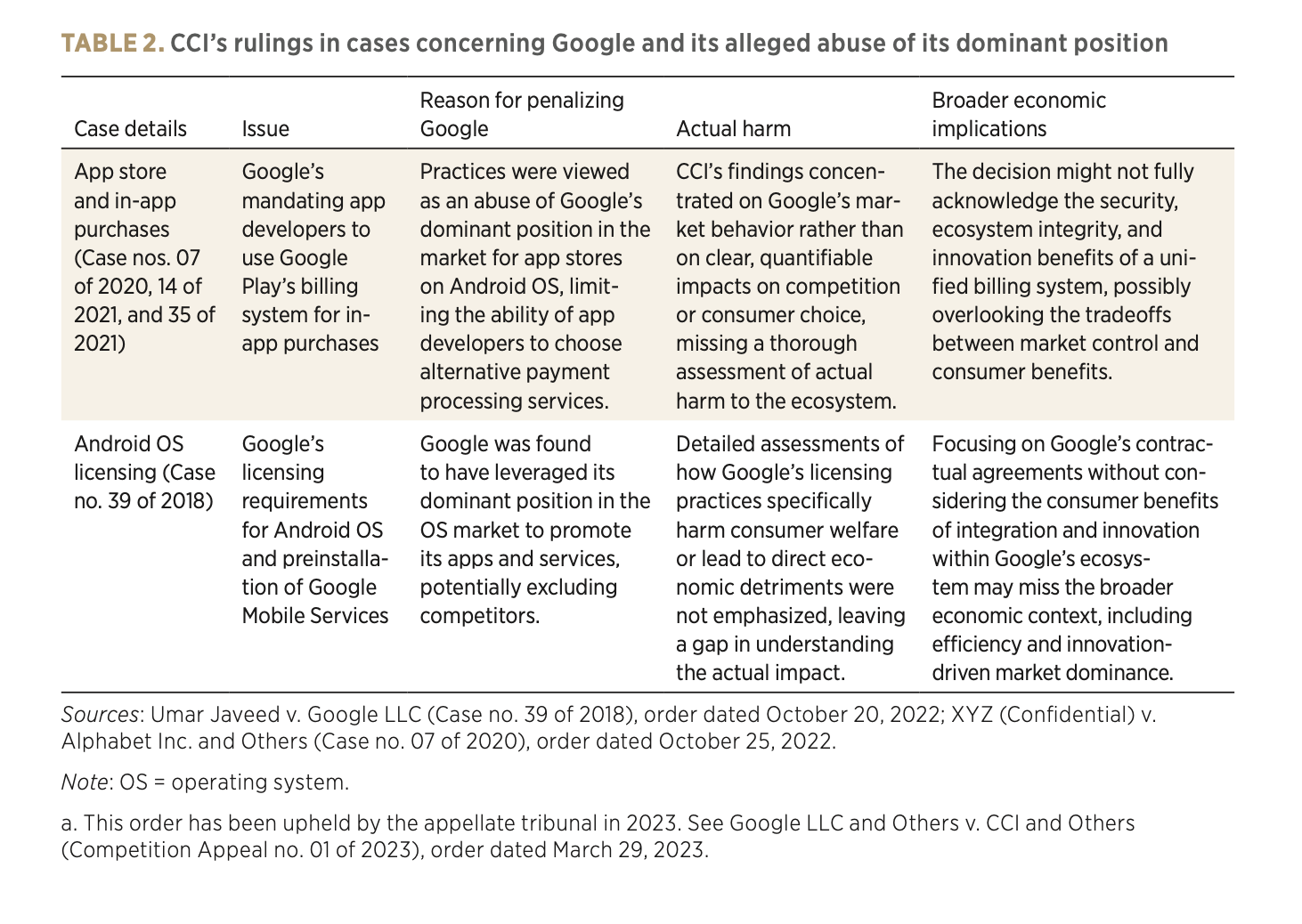

Yet CCI’s application of the relevant turnover principle has varied. It has been critical of applying the principle in certain abuse of dominance cases, particularly those involving big tech companies. In matters that dealt with Google’s dominant position in markets for licensable operating systems for smart mobile devices, app stores for Android, and general web-search services, CCI criticized the concept of relevant turnover. CCI held that in multisided digital platforms, in which products and services are intricately intertwined and some sides may be free to users, the entire platform should be considered one unit, and the revenue generated by the platform should be seen as a whole. In all such instances, CCI levied a penalty on Google based on total turnover, to the tune of Rs 24.1 billion, or approximately US$304 million,[44] which is two and one-half times what the government of India spent on publicizing its schemes in the print media over four years from 2019 to 2023.[45]

In the 15 years since the law came into effect, no clear penalty guidelines were issued that could make the penalty amount predictable. Therefore, India’s penalty rates for anticompetitive conduct have remained arbitrary and have varied from case to case, with no clear, consistent standard.

The 2023 amendment to the 2002 act inserted an explanation that changed the definition of turnover to mean global turnover.[46] This change dramatically escalates potential antitrust penalties. While calculating fines on the basis of total turnover was already problematic, using global turnover is excessive. CCI can now consider an enterprise’s turnover from all its operations, in India and globally, as the basis for levying penalties.

The global turnover approach could lead to excessive penalties that are not commensurate with the degree of harm caused in India. It may also result in unfair outcomes and discrimination between domestic companies and entities with global operations, as export turnover or turnover with no nexus to India could be included in the calculation of penalties for global firms. It could also adversely affect the few domestic companies that have international operations and reach.

The shift to global turnover could have significant implications for big tech companies facing abuse of dominance allegations. The platform-based total turnover approach adopted by CCI in cases involving multisided digital markets, combined with the global turnover amendment, could lead to substantial penalties, even if the harm caused in India is limited.

Guidelines 2024

Only in March 2024 did CCI issue the Determination of Monetary Penalty Guidelines of 2024, which capped the penalty at 10 percent of global turnover, aiming to make it proportional to the degree of the violation. However, an explicit clause in Section 28 of the 2002 act stating that turnover will mean global turnover sends a negative signal to global enterprises. While the new guidelines clarify the calculation process, their practical implementation and impact on penalty calculations remain uncertain, given CCI’s history of inconsistent interpretation of “turnover” and calculation of penalties.

V. On Big Tech Firms: Is It a Witch Hunt?

The challenges in determining dominance and abuse of dominance are not limited to traditional industries but extend to rapidly evolving digital markets in which a few players tend to dominate. The products in these markets are often intangible, services are interconnected, and the marketplace is virtual. The business models characterizing these markets are multisided, with platforms as intermediaries linking distinct market participants.

Digital markets are underpinned by data-driven network effects, meaning the value of the product or service is magnified as more people use it. User data fuel enhancements in service quality, thereby creating a feedback loop that can lock in users and quickly increase a platform’s dominance.

For example, smartphones with Google’s Android operating system (OS) are preinstalled with the Google Play store, Google’s app store. Along with the Play store, such smartphones also have apps like Google Play Music and Google Search either preinstalled or prominently featured on the app store. This illustrates two common, potentially anticompetitive practices in digital markets: tying and self-preferencing. Tying refers to selling a product (the OS) on the condition that the buyer must also use another product (the app store). Self-preferencing involves a vertically integrated company favoring its products or services over those of its competitors; in this case, Google features its apps more prominently.

The example also highlights how data-driven network effects and multisided platforms play a role in these practices. As more users adopt the OS and use the app store, it becomes increasingly attractive for app developers to create apps for that ecosystem. The new apps, in turn, attract more users, creating a self-reinforcing cycle. With control over the OS and the app store, the platform owner can leverage these network effects to promote its apps.

But who is affected? Most of the products on the app store on such platforms are available for free, with the option to get upgraded versions for a price. For the end consumers, harm in the form of high prices is unlikely. However, for app developers or advertisers who have to use the platform to reach the end consumer, Google’s licensing policies for app developers matter, especially if Google is also competing with them through the app store. However, Google has faced stiff competition in various markets, even from its own products. For example, Google Play Music, Google’s music and podcast streaming service, was eventually shut down because of competition from Apple Music, Spotify, and YouTube, the latter being a subsidiary of Google. This example demonstrates that Google’s success is not guaranteed and that the company must continually innovate and compete to maintain its position in the market.

However, if Google’s policies cause competing apps to exit the market, leaving end consumers with limited options in its app store, does that qualify as harmful? Not necessarily. If app developers can switch platforms and end consumers can easily switch to phones with different operating systems and app stores that offer more options, Google’s ability to leverage power is limited. In such a scenario, Google may even lose users on different market sides if it fails to provide a competitive offering. Some of these issues have come up in CCI’s investigations. For a snapshot of CCI’s interventions, see table 2.

A common thread is that CCI’s analysis focused more on Google’s market conduct than on tangible, measurable harms to competition or consumer welfare. For instance, in assessing Google’s licensing and preinstallation requirements for Android, CCI focused on Android’s dominance in the “licensable mobile operating system (OS) market in India.”[47] This narrow definition exaggerated Google’s market power by not considering the broader ecosystem, including competition from iOS (deemed different because it is not licensable) and the benefits of integrated platforms that enhance user experience and security. To CCI, it was immaterial that most of Google’s bundled services are offered free to consumers. There is often no cost-based difference between Google’s preinstalled apps and alternative third-party apps for users.

Instead, CCI noted the high entry barriers to the mobile OS market, emphasizing the substantial investments needed to develop a new OS. This perspective, though sympathetic to new entrants, overlooks the fact that dominant players such as Google have established ecosystems that are difficult to penetrate not only because of restrictive practices but also because of their extensive adoption, their network effects, and a high level of innovation protected by patents.

While CCI criticized Google for its market advantage on account of its vast user base and extensive app compatibility, these advantages are outcomes of Google’s early initiatives, ongoing innovation, and effectiveness in attracting app developers rather than the result of anticompetitive practices. Penalizing Google for leveraging legitimate competitive advantages could unfairly punish success. In fact, despite its size, access to vast data, and investment in artificial intelligence platforms, Google is not a front-runner in artificial intelligence.

The mobile OS market has witnessed successful new entries, such as iOS, indicating that while entry is challenging, the high barriers are not insurmountable. Consumers also have the option to switch to phones that come with customized OSs built on stock Android and that compete with Android, such as Samsung’s One UI and OnePlus’s OxygenOS. This example illustrates the need for a nuanced regulatory approach that differentiates between anticompetitive practices and legitimate business processes born of innovation and market acumen.

In digital markets, companies often compete for the market rather than within the market.[48] Companies compete fiercely to become the dominant player in a particular segment. Once they achieve that position, they face competitive pressure from new entrants and adjacent markets. This dynamic competition ensures that dominant companies must continuously innovate to maintain their position.[49]

The recently proposed digital competition bill risks disrupting this dynamic order in digital markets.[50] The bill grants CCI broad discretion to regulate some digital firms purely on the basis of their size and to impose obligations on them without clearly defining the criteria for such obligations. Demonstrable harm to competition or consumers is not a criterion.

The bill imposes blanket prohibitions on certain business practices of the regulated firms, such as self-preferencing, tying, bundling, and using nonpublic data from business users to compete with them. While these practices may raise concerns in some cases, an outright ban fails to consider their potential procompetitive effects and consumer benefits.

For example, imagine that Tesla wants to set up a gigafactory in India to produce self-driving cars. The gigafactory would be a manufacturing unit and a digital factory, integrating advanced technologies such as robotics, machine learning, and data analytics into production. However, given the vagueness of the bill and the potential ambiguity in subsequent regulations, the gigafactory could be subject to ex ante regulations, placing unreasonable compliance burdens on the company.[51]

Furthermore, the bill’s prohibitions on bundling and tying could limit Tesla’s ability to integrate its various products and services, such as its charging infrastructure, software updates, and future ridesharing possibilities, into a seamless and convenient user experience. These restrictions could harm consumer welfare and discourage the company from investing and innovating in the Indian market.

Aligning regulatory actions with the realities of the digital market is crucial. An approach that recognizes the value of integrated platforms and the potential for emerging competitive dynamics could better serve the long-term interests of consumers and the broader digital ecosystem.

VI. Recommendations

India needs large enterprises as they can play a crucial role in its economy. They possess the capacity for substantial investments, driving productivity and economies of scale. These firms can catalyze the growth of small and medium enterprises through backward linkages, facilitate technology adoption, and promote global integration. Moreover, with 1.2 million Indians entering the workforce each month, the employment opportunities generated by large-scale enterprises are vital.[52] However, India’s economic policies (including the competition law) have historically been anti–big business and belie these economic realities.

For example, the anti–big business bias in the competition law could affect India’s aviation industry, which has been growing but has also received attention for the rising concentration in the domestic market.[53] In March 2023, the parliamentary standing committee on transport, tourism, and culture recommended competition regulation to address rising airline ticket prices attributable to market concentration in the aviation industry.[54] All eyes are on the dominant airlines, IndiGo and Tata Group’s Air India, because of their combined domestic market share of 81 percent, despite CCI’s approval of the merger of Air India and Vistara.

This approach fails to recognize the true culprits behind the industry’s woes—tough entry barriers, burdensome compliance costs, high fuel prices, and inefficient public sector–owned airport infrastructure—which drive up operational costs for existing and potential airline companies. The aviation industry is subject to a complex web of laws, some dating back to 1934, and delegated legislation, executive-issued directives, and six governing bodies.[55] Despite some liberalization, bottlenecks have persisted, such as the requirement to physically reexport and reimport aircraft when transferring leases between Indian airlines, which was only removed in late 2021.[56] To encourage domestic carriers, foreign airlines have not been issued flying rights in the domestic market since 2014.

These regulatory hurdles and infrastructure inefficiencies have led to prohibitively high operational costs, resulting in consistent losses for the airline industry over the past five years, extending to even before the COVID-19 pandemic. In May 2023, Go First, a private airline with 8 percent market share, folded under the weight of these challenges despite having been penalized for price fixing by CCI in 2018.

Without an effects-based assessment under Section 4, CCI is more likely to deem the two airlines that have captured much of the market share dominant. Any practice—such as rebates on air prices offered—may be deemed an abuse of their dominant position, even if it is part of their marketing strategy or meant to increase aircraft use.

Competition law should, therefore, not be used as a sledgehammer to go after big business to increase contestability in markets. Instead, Indian regulators should use a scalpel to create a more robust and effective competition law regime in India. To this end, I propose the following recommendations:

- Section 4 of the 2002 act should be amended to mandate that adverse effects of a dominant firm’s conduct in the market be scrutinized in all abuse of dominance cases. The amendment would ensure that CCI focuses on practices that demonstrably harm competition. It would make the law consistent and help avoid protracted litigation arising from a formalistic interpretation of the law. CCI should employ a consistent and evidence-based approach across all sectors, ensuring that dominant market players, regardless of industry, are assessed for the actual anticompetitive harm of their actions. CCI should focus on curbing abuses that demonstrably harm competition and consumer welfare rather than on preemptively regulating companies on the basis of their size or market share. When assessing the effects or harm, CCI should assess evidence of the firm’s ability to profitably raise prices while simultaneously restricting output in the market to the detriment of consumers.

- Explanation 2 of Section 27(b) of the 2002 act should be omitted. With the penalty guidelines clarifying that 10 percent global turnover will be the maximum cap, explanation 2, which states that “turnover” would mean “global turnover derived from all the products and services,” is redundant. It sends a wrong message about India’s disproportionate and unfair treatment of global firms. Along with omitting the explanation, CCI should ensure consistency by adhering to the relevant turnover principle.

- Section 28, which empowers CCI to break up dominant firms, should be omitted from the 2002 act. It is a flawed transplant and grossly excessive. The potential for misuse of Section 28 becomes even more apparent when we consider specific cases. If Air India’s dominance in the aviation sector is taken umbrage to, could CCI use the provision to break up the Tata Group, given the size of the conglomerate? Such a scenario would not only be detrimental to the group but could also have far-reaching consequences for India’s economic landscape and its ability to foster globally competitive enterprises.

Implementing these reforms would push Indian regulators to evolve beyond their reflexive suspicion of size. This change is a necessary condition.

Notes

[1] The working provisions dealing with anticompetitive agreements and abuse of dominance came into effect only in 2009, and those relating to mergers in 2011, after constitutional challenges were settled in 2005 (Brahm Dutt v. Union of India (2005) 2 SCC 431). Amendments were subsequently enacted in 2007, 2009, and 2023.

[2] Herbert J. Hovenkamp, “The Slogans and Goals of Antitrust Law” (All Faculty Scholarship 2853, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, October 17, 2023).

[3] While antitrust discussions often refer to “consumer welfare,” courts and experts typically measure changes in output or prices, inferring welfare effects from those metrics. Hovenkamp contends that an output-focused standard benefits all groups by considering whether firms’ conduct decreases market-wide output, which would increase prices and primarily burden consumers. Such a “true consumer welfare” standard can encourage markets to produce the highest sustainable output. Hovenkamp, “The Slogans and Goals of Antitrust Law.”

[4] Meru Travel Solutions Private Limited v. Uber India Systems Private Limited (Case no. 96 of 2015), order dated February 10, 2016.

[5] Meru Travels Solutions Private Limited v. Competition Commission of India (Appeal no. 31 of 2016), order dated December 7, 2016.

[6] Uber India Systems Private Limited v. Competition Commission of India (2019), 8 SCC 697, order dated September 3, 2019.

[7] Meru Travel Solutions Private Limited v. Uber India Systems Private Limited (Case no. 96 of 2015), order dated July 14, 2021.

[8] Viral V. Acharya, “India at 75: Replete with Contradictions, Brimming with Opportunities, Saddled with Challenges,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, no. 1 (2023): 185–288.

[9] The NIC-2-digit code refers to the two-digit level of India’s National Industrial Classification system, using a pair of numbers (00-99) to categorize economic activities across various sectors of the Indian economy. It facilitates statistical analysis, policy formulation, and cross-sectoral comparisons of economic data.

[10] Acharya, “India at 75.” On problems with methodologies for calculating industrial concentration in India, see Gaurav Somenath Ghosh and Subhashish Gupta, “Industrial Concentration in India” (Research Paper 677, Indian Institute of Management–Bangalore, March 29, 2023).

[11] Trusts were monopolies controlling entire national markets. By 1904, 318 trusts held 40 percent of US manufacturing assets (US$7 billion). Trustbusting peaked from 1904 to 1912 under Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft, who filed 44 and 90 antitrust suits, respectively. Notable cases included breaking Standard Oil into 34 companies (1911). “Targeting the Trusts,” in The American Yawp, vol. 2, ed. Joseph Locke and Ben Wright (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2023).

[12] Section 3, Competition Act, 2002.

[13] More specifically, Section 4(2)(c)–(e), Competition Act, 2002.

[14] M/s Kansan News Private Limited v. M/s Fast Way Transmission Private Limited and Others (Case no. 36 of 2011), order dated July 3, 2012.

[15] Section 19(4)(1), Competition Act, 2002.

[16] Explanation (a) to Section 4, Competition Act, 2002.

[17] Section 19(6) of the Competition Act, 2002, discusses 10 factors, of which any or all are useful in determining the “relevant geographic market.” These factors are regulatory trade barriers, local specification requirements, national procurement policies, adequate distribution facilities, transport costs, language, consumer preferences, need for secure or regular supplies or rapid after-sales services, characteristics of goods or nature of services, and costs associated with switching supply or demand to other areas. Section 19(7) of the act lists eight factors, of which any or all are useful in determining the “relevant product market.” These factors are the physical characteristics or end use of goods or nature of services, price of goods or services, consumer preferences, exclusion of in-house production, existence of specialized producers, classification of industrial products, costs associated with switching demand or supply to other goods or services, and categories of customers.

[18] Section 19(4) of the Competition Act, 2002, lists 13 factors, of which any or all are useful in determining a firm’s “dominant position.” These factors are the firm’s market share, the firm’s economic power, the size and resources of the firm, the size and importance of its competitors, dependence of consumers on the firm, entry barriers, market structure, relative advantage, social obligations and costs, vertical integration or sale or service network, statutory monopoly, countervailing buying power, and any other factor that CCI may deem as relevant.

[19] In re: XYZ v. Association of Man-Made Fibre Industry in India (Case no. 62 of 2016), order dated March 16, 2020.

[20] Informant (Confidential) v. Grasim Industries Limited (Case no. 51 of 2017, Case no. 54 of 2017, Case no. 56 of 2017), order dated August 6, 2021.

[21] Aditya Bhattacharjea, “Abuse of Dominance under the Competition Act: The Need for a Competitive Effects Test,” Indian Competition Law Review 8, no. 2 (2020): 36–43.

[22] Section 4(2)(a)(ii), Competition Act, 2002.

[23] Sections 4(2)(a)(i) and 4(2)(d), Competition Act, 2002.

[24] Section 4(2)(a)(ii), Competition Act, 2002.

[25] Section 4(2)(e), Competition Act, 2002.

[26] Explanation to Section 4(2)(a)–(b), Competition Act, 2002.

[27] Payal Malik, Neha Malhotra, Ramji Tamarappoo, and Nisha Kaur Uberoi, “Legal Treatment of Abuse of Dominance in Indian Competition Law: Adopting an Effects-Based Approach,” Review of Industrial Organization 54 (2019): 435; Bhattacharjea, “Abuse of Dominance under the Competition Act.”

[28] Section 4(2)(c), Competition Act, 2002.

[29] M/s Fast Way Transmission Private Limited and Others v. Competition Commission of India and Others (Appeal no. 116 of 2012), order dated May 2, 2014.

[30] Approximately US$1.38 million.

[31] Competition Commission of India v M/s Fast Way Transmission Private Limited and Others (2018), 4 SCC 316, para. 11.

[32] Sonam Sharma vs. Apple Inc and Others (Case no: 24 of 2011), order dated March 19, 2013.

[33] Google LLC and Others v. CCI and Others (Competition Appeal no. 01 of 2023), order dated March 29, 2023.

[34] Ministry of Corporate Affairs, Report of Competition Law Review Committee (New Delhi: Government of India, 2019), 108.

[35] Competition Commission of India v. Schott Glass India Private Limited, Civil Appeal 5843/2014 (pending). Also, see Google LLC and Others v. CCI and Others (Competition Appeal no. 01 of 2023); Bhattacharjea “Abuse of Dominance under the Competition Act.”

[36] Maureen K. Ohlhausen and John M. Taladay, “Are Competition Officials Abandoning Competition Principles?,” Journal of European Competition Law and Practice 13, no. 7 (October 2022): 469.

[37] These jurisdictions include Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Germany, Hungary, the Republic of

Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, Singapore, the Slovak Republic, South Africa, and Spain. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, “Latin American and Caribbean Competition Forum, Session I: Fining Methodologies for Competition Law Infringements—Background Note,” September 27, 2019.

[38] European Commission, “Guidelines on the Method of Setting Fines Imposed Pursuant to Article 23(2)(a) of Regulation No 1/2003” [2006] OJ C210/2.

[39] Competition and Markets Authority, “CMA’s Guidance as to the Appropriate Amount of a Penalty,” CMA73, December 16, 2003.

[40] Competition and Consumer Commission of Singapore, “CCCS Guidelines on the Appropriate Amount of Penalty in Competition Cases,” February 1, 2022.

[41] Section 2(y), Competition Act, 2002.

[42] Section 27 came into effect in 2009.

[43] Excel Crop Care Limited v. Competition Commission of India and others (2017) 8 SCC 47.

[44] Matrimony.com Limited and Another v. Google LLC and Others (Case nos. 07 and 30 of 2012), order dated February 8, 2018; Umar Javeed v. Google LLC (Case no. 39 of 2018), order dated October 20, 2022; XYZ (Confidential) v. Alphabet Inc. and Others (Case No. 07 of 2020), order dated October 25, 2022.

[45] Press Trust of India, “Govt Spent ₹967.46 Crore on Advertisements in Print Media from 2019–20 to 2023–24,” The Hindu, December 19, 2023.

[46] Explanation 2 to Section 27(b), Competition Act 2002.

[47] Umar Javeed v. Google LLC (Case no. 39 of 2018), order dated October 20, 2022.

[48] Damien Geradin and Dimitrios Katsifis, “The Antitrust Case against the Apple App Store (Revisited)” (TILEC Discussion Paper 2020-35, Tilburg Law and Economics Center, Tilburg University, Tilburg, Netherlands, December 7, 2020).

[49] David S. Evans, “Why the Dynamics of Competition for Online Platforms Leads to Sleepless Nights but Not Sleepy Monopolies” (working paper, Jevons Institute for Competition Law and Economics, University College London, 2017).

[50] Ministry of Corporate Affairs, Report of the Committee on Digital Competition Law (New Delhi: Government of India, 2024), annexure IV.

[51] Shreyas Narla and Shruti Rajagopalan, “India’s Proposed Digital Competition Framework: The License Raj by Another Name” (Mercatus Policy Comment, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Arlington, VA, July 2024).

[52] Acharya, “India at 75.”

[53] Anu Sharma, “Is India’s Aviation Market Headed for a Duopoly?,” Mint, June 21, 2023; Sumanta Sen, “Two Airlines Dominate India’s Growing Market,” Reuters, July 24, 2023; Manu Balachandran, “Between Air India and IndiGo, India’s Skies Are Headed for a Duopoly. What’s This New Reality?,” Forbes India, September 21, 2023.

[54] Rajya Sabha, 339th Report on the Demand for Grants of Ministry of Civil Aviation (2023–2024) (Department-Related Parliamentary Standing Committee on Transport, Tourism and Culture, 2023).

[55] The governing bodies are the Ministry of Civil Aviation, Directorate General of Civil Aviation, Bureau of Civil Aviation Security, Aircraft Accidents Investigation Bureau, Airports Economic Regulatory Authority of India, and Airports Authority of India.

[56] Ministry of Civil Aviation, “Atmanirbhar Bharat in Aviation Sector,” press release, July 28, 2021; Anand Shah, Haseena Tapia Shahpurwalla, Rishiraj Baruah, and Saptarshi Bhuyan, Aviation 2023 (AZB & Partners, 2023), https://web.archive.org/web/20230531013308/https://www.azbpartners .com/ bank/aviation-law-2023/.