The Indian economy has come a long way from the depths of the 1970s, when the state’s stranglehold on economic activity plunged growth rates to low levels averaging just over 3% from 1965 to 1980.[1] A repressive trade regime rendered India a near autarky, with trade in goods dropping to less than 10% of GDP. With subsequent domestic and external reforms, the most dramatic of which were initiated in the early 1990s, the Indian economy took off, with growth rates rising rapidly and reaching a high of over 8% during the 2000s and averaging around 7% in recent years. India is now the third-largest economy in the world. However, India’s footprint in international trade and in international factor flows remains small. Specifically, India accounts for only about 2% of world trade and hosts only a little over 1% of the stock of global foreign direct investment.[2] This paper argues that these modest outcomes are the result of India’s domestic and external policy choices, structural difficulties relating to the allocation of the labor force, and a stalled international economic environment. Improving trade performance and utilizing global markets to support economic development are urgent priorities. This paper suggests that India explore trade liberalization on a unilateral basis or in the context of well-designed trade agreements to improve productivity, expand its international market access, and leverage the economic possibilities offered by regional global value chains (GVCs).

India’s inability to expand its international economic engagement is largely a function of its own policy choices and structural challenges. Despite significant liberalization in recent decades, several domestic shortcomings, including infrastructural weakness, challenging labor regulations, difficulties in land acquisition, and a complex regulatory and bureaucratic environment have hampered India’s competitiveness and growth. India’s development trajectory has faced significant pressures that, in turn, are reflected in its trade performance. Specifically, India possesses an abundance of low-skill workers, around half of whom are employed in the relatively unproductive agriculture sector, which generates only around 15% of output. Despite the reforms undertaken in recent decades, Indian manufacturing has been stagnant, accounting for about 15% of GDP for the last couple of decades. Surprisingly, the economy has experienced an expansion of the services sector, including high-tech services, reflecting a disconnect between India’s production patterns and its comparative advantage from the abundance of low-skill labor.

While the impressive growth of the high-tech services sector in India has been justly celebrated, the expansion of services, especially high-tech services, does not in itself offer a sustainable path forward. The vast majority of workers in the agricultural sector do not have the skills necessary for employment in the high-tech-services sector. They will need to transition into jobs in manufacturing. Any reasonable growth strategy for India must therefore consider the large number of low-skill workers in the labor force and the need to increase their employment in sectors other than agriculture. A large global market that demands low-skill manufactures offers one solution to this problem. Large markets allow production at scale and thus result in lower costs and greater competitiveness. India’s penetration of global markets is still quite small, even in sectors of traditional strength. Thus, while global exports of clothing were close to US$500 billion in 2018, India exported less than US$20 billion. Overall, India accounts for less than 2% of global exports, suggesting that there is very substantial scope for India to follow an export-led growth strategy.

Additionally, India faces several important challenges on the external front. The multilateral trade system—overseen by the World Trade Organization (WTO)—has stagnated, unable to advance the Doha Round of negotiations that began nearly two decades ago. Expanding market access for India’s exporters through multilateral liberalization will be a difficult task. Relatedly, while the multilateral WTO process has stalled, preferential trade agreements (PTAs) that contravene the nondiscriminatory spirit of the WTO (as enshrined in Article I of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade [GATT]) have grown in prominence.[3] Since the early 1990s there has been a proliferation of preferential agreements, such as the European Union (EU) and the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) (recently redesigned and renamed the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement). Indeed, hundreds of such PTAs have been signed in the last three decades. These have led to a fragmentation of the world trade system and have complicated and disadvantaged Indian access to markets worldwide. Further, globalization is now subject to several retrograde pressures. Among other countries, the United States, once a champion of the rules-based international trade system, in recent years has taken aggressive and unusual stances in violation of WTO norms by imposing tariffs on its trade partners (especially China) on contrived national-security grounds, has backed out of some nearly completed negotiations (such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership), and has demanded renegotiation of existing agreements (namely NAFTA) while threatening outright exit from the WTO itself. These unilateral assertions of US power have upended traditional mechanisms for negotiation and exchange in the system, raising fundamental questions about the future of the global order and the necessary steps to achieve progress within it. From the standpoint of India’s trade and aspirations, developments such as the US–China trade war may open up specific economic opportunities, but from a systemic standpoint, none of the recent changes in the global system can be seen as particularly positive.[4]

The rest of this paper proceeds as follows. The next section describes India’s preferential trade agreements and their consistently modest outcomes. The paper then discusses the reasons for India’s limited success in enhancing trade through trade agreements. Next, it explains how global value chains affect trade agreements. Finally, the paper provides policy recommendations to enhance India’s trade competitiveness and market access and offers concluding remarks.

India’s Trade Agreements

In recent years, India too has negotiated several PTAs.[5] Some are bilateral agreements with individual partner countries, while others are plurilateral agreements with multiple countries. India’s bilateral agreements are with Afghanistan, Bhutan, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Nepal, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and the Republic of Korea (South Korea). India has entered plurilateral agreements with the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN) through the India–ASEAN Free Trade Agreement and with the MERCOSUR countries (Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, and Paraguay) through the MERCOSUR–India trade agreement. Finally, India is also a member of the Asia-Pacific Trade Agreement (involving Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, China, South Korea, and Laos) and the South Asia Free Trade Agreement (involving Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Sri Lanka, India, the Maldives, Nepal, and Pakistan). The impact of these trade agreements on India’s trade outcomes is a matter of significant policy interest. Proponents of these agreements hoped that increased market access would expand India’s exports to its partner countries, while opponents feared that the agreements would widen India’s trade deficits. As this paper argues, neither side was proved right: India’s bilateral trade agreements have, thus far, had a minimal impact on its international trade. Specifically, trade under India’s trade agreements has not grown any faster than India’s trade outside its agreements. Importantly, this outcome occurred largely because India’s agreements were relatively shallow; they have entailed only very modest liberalization of tariffs and other trade barriers. From a political-economy perspective, this is not especially surprising since the very same lobbies that oppose trade liberalization at the multilateral or unilateral level also oppose liberalization undertaken on a preferential basis. Further, India’s trade outcomes under its PTAs have not improved because bureaucratic complexity means that preference use within PTAs tends to be quite shallow. Against this historical background, India’s share in global value chains is low. Participation in regional GVCs will likely require India to engage in regional PTAs with significant trade liberalization. Whether domestic politics and international geopolitics will permit such a step is yet to be seen.

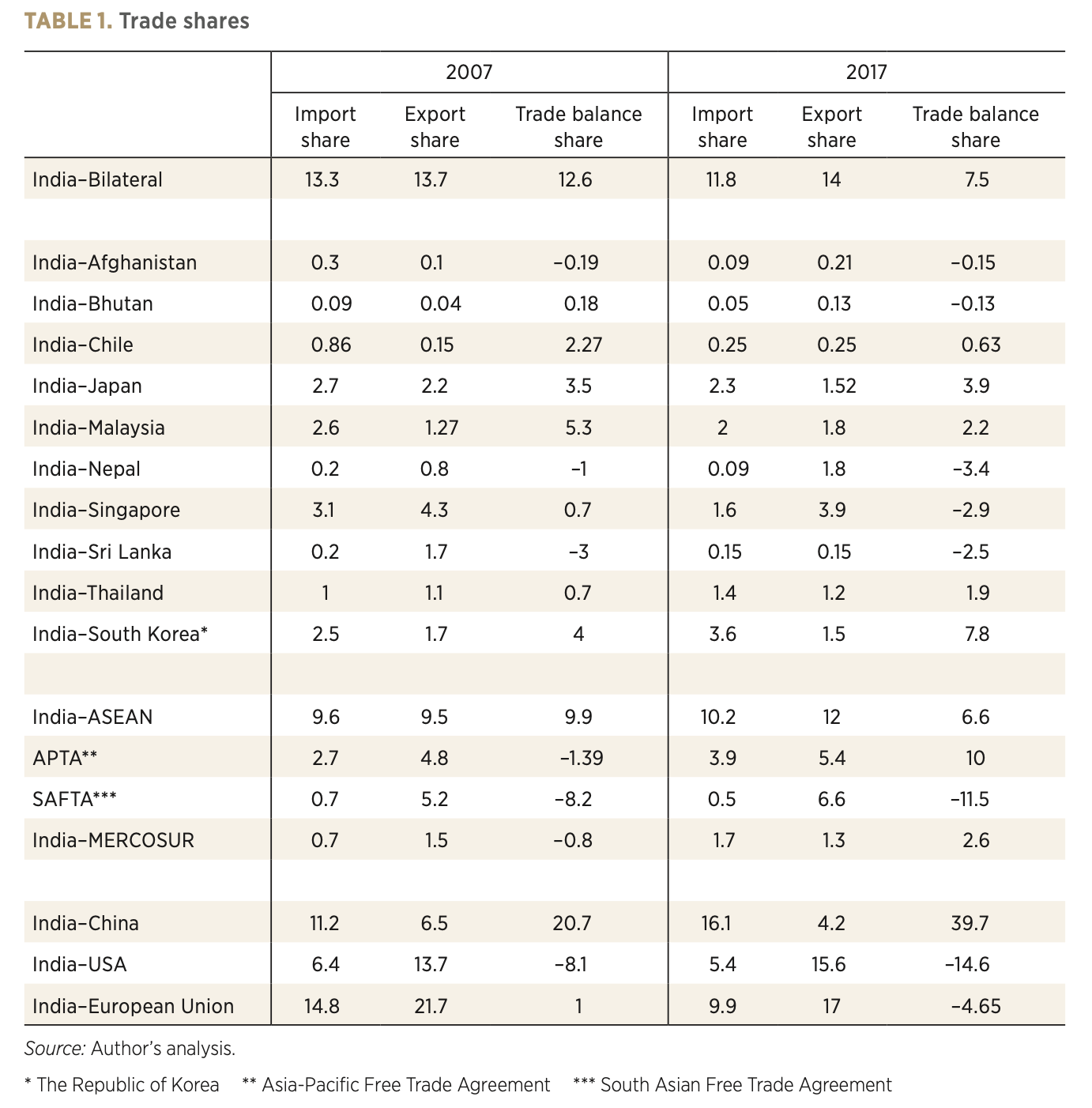

Table 1 shows India’s import and export shares in 2007 and 2017 with countries with which it has bilateral agreements. It also provides information on trade trends under India’s plurilateral agreements: ASEAN, the Asia-Pacific Trade Agreement, the South Asia Free Trade Agreement, and MERCOSUR.[6] Finally, for purpose of comparison, table 1 reports information on trade between India and the United States, the EU, and China.

It is evident that trade between India and most of these partner countries has stayed steady for many years. Consider, first, trade between India and its bilateral-agreement partners: overall imports with these countries stood at 13.3% of total imports in 2007 and moved to 11.8% by 2017. Exports to these countries stood at 13.7% in 2007 and moved to 14% by 2017. Thus, trade between India and its bilateral partners has remained steady relative to India’s global trade patterns. Trade with the larger partners among the bilateral-agreement trade partners—South Korea, Japan, Malaysia, and Singapore—has also been remarkably steady, especially in the aggregate: the slight increase in import share from South Korea is offset by reductions in import shares from Japan, Malaysia, and Singapore. India’s trade under plurilateral agreements—notably

India–ASEAN and India–MERCOSUR—has also been mostly steady. Trade with ASEAN countries rose slightly (the import share rose from 9.6% to 10.2%, and the export share rose from 9.5% to 12%). India–MERCOSUR did not change by much either. MERCOSUR’s import share rose from 0.7% to 1.7%, and its export share dropped slightly from 1.5% to 1.3% of overall exports. Thus, India’s trade share with its bilateral and plurilateral partners did not rise significantly from 2007 to 2017.[7]

One frequently expressed concern is that India’s trade agreements have led to an expansion of its trade deficits with its PTA partners. However, the data indicate otherwise. Trade deficits with India’s bilateral partners accounted for 12.6% of the overall trade deficit in 2007. In 2017, they accounted for a considerably smaller 7.5%. Similarly, India’s trade with ASEAN and MERCOSUR accounted for 9.1% of the total trade deficit in 2007 and 9.2% in 2017. Thus, while India’s trade deficits widened in nominal-dollar terms, its PTAs do not account for an appreciably larger fraction of its trade deficit than they did before.

Trade shares within India’s agreements are relatively steady, but what does trade look like at the sectoral level? Are there sectors in which the growth of trade with trade-agreement partners is significantly greater than with other trade partners? Have any sectors suffered from a surge in imports from partners?

An examination of disaggregated three-digit trade data from 2007 to 2017 helps to identify sectors in which trade growth was faster under trade agreements than outside them. Sectors in which trade grew faster than 25% within India’s bilateral agreements relative to trade with the world amounted to about US$18 billion of imports and US$10.2 billion of exports in 2017. For ASEAN, the corresponding figures are US$15 billion of imports and US$26 billion of exports. For sectors in which trade within bilateral agreements more than doubled relative to trade with the world, the volume of trade amounted to US$4.8 billion of imports and US$3 billion of exports. For ASEAN, the corresponding 2017 figures are US$7 billion and US$10 billion. Taken together, this amounts to US$12 billion of imports and US$13 billion of exports in 2017. One can conclude that sectoral import surges did not exceed export surges and that these surges were small compared to the overall volume of trade (6.5% of overall trade and 3.5% of overall imports).

Explaining the Modest Trade Growth

The preceding discussion suggests that trade under India’s trade agreements did not grow any faster than trade outside its agreements. This finding offers no comfort to either supporters of the agreements or its detractors. But it does raise the question of why so many agreements have had such modest effects. The primary explanation is that India’s agreements have brought less liberalization than expected. Importantly, India notified the WTO of most of its agreements—except for agreements with Japan and Singapore—under the Enabling Clause. Unlike the WTO’s Article XXIV agreements, which require liberalization on “substantially all trade,” agreements notified under the Enabling Clause were generally of partial scope and often brought limited liberalization. The agreements have also included a range of implementation schedules, with liberalization by India and its partners taking place over several years after India first notified the GATT of the agreements. Thus, for instance, while liberalization under the India–Japan trade agreement began in 2011, implementation has been completed for only about 23% of the tariff lines. For 63% of goods liberalized under the agreement, tariff liberalization by India was to be implemented by 2021. Another 14% of goods were excluded from the agreement altogether. Similarly, under the India–South Korea agreement, signed in 2010, only about 8% of tariff lines were fully eliminated prior to 2017. Over 60% of the tariff lines were to be liberalized by India by 2017, and about 20% were excluded from elimination altogether. Similarly, the India– ASEAN agreement, which began liberalization in 2010, set out to eliminate nine thousand tariff lines, but this was only to be completed by 2016.

The trade outcomes under India’s PTAs are mirrored, to some extent, in outcomes under preferential agreements in the rest of the world.[8] Thus, the World Trade Report of 2011 shows that while the value of trade has grown between PTA members, much of this trade is not taking place on a preferential basis.[9] Consider trade between PTA partners, which made up around 18% of world trade in 1990 and rose to 35% by 2008 (in both cases, the figures exclude intra-EU trade). When the EU is included, intra-PTA trade rose from about 28% in 1990 to a little over 50% in 2008. The value of intra-PTA trade rose from US$537 billion in 1990 to US$4 trillion by 2008, excluding the EU, and from US$966 billion to nearly US$8 trillion when the EU is included. This might suggest that, by now, a large share of world trade is taking place between PTA members. However, as the World Trade Report points out, these statistics vastly overstate the extent of preferential trade liberalization and, thus, the extent of preferential trade. This is because much of the trade between PTA members is in goods on which they impose most favored nation (MFN) tariffs of zero in the first place. Goods subject to high MFN tariffs are also often subject to exemptions from liberalization under PTAs, so the volume of trade that benefits from preferences is, on average, quite low. Specifically, World Trade Report calculations indicate that despite the recent explosion in PTAs, only about 16% of world trade takes place on a preferential basis (the figure rises to 30% when intra-EU trade is included). Furthermore, less than 2% of trade (4% when the EU is included) takes place in goods that receive a tariff preference greater than 10%.

For example, well over 50% of South Korean imports enter India with zero MFN tariffs. South Korea offers preferences on about 10% of its imports but a preference margin greater than 10% on virtually none of its imports. A similar picture emerges on the exporting side. One country that has actively negotiated PTAs is Chile, and 95% of Chilean exports go to PTA partners. However, only 27% of Chilean exports are eligible for preferential treatment, and only 3% of Chile’s exports benefit from preference margins greater than 10%. Overall, most PTA trade takes place under zero MFN tariffs. Only a small fraction of imports enters on a preferential basis, especially from outside the EU and NAFTA. Taken together, these statistics suggest that the extent of trade liberalization through PTAs has been quite modest despite the large number of PTAs that have been negotiated—a picture similar to that of liberalization under Indian PTAs.

None of this should be too surprising. It is widely understood that a major factor working against trade liberalization is the opposition of import-competing lobbies, so it is unclear why lobbies that oppose trade liberalization at the multilateral or unilateral level would support liberalization undertaken on a preferential basis. We should, therefore, expect that political lobbies will mostly permit preferential agreements in which their rents are protected, either through access to partner-country markets or, more simply, through an exemption of liberalization on imports of those goods that compete with their own production, suggesting complementarities between MFN status and PTA tariffs.[10] This applies to India, where, as noted, liberalization under India’s agreements has been quite limited, and exclusions and sensitive-goods categories have been maintained in each trade negotiation.

In addition to the shallow liberalization, use of trade preferences under trade agreements may be cumbersome. Specifically, Saraswat, Priya, and Ghosh (2017) have suggested that preference use under India’s PTAs is only about 25% because of a lack of information about preferences, low margins of preference, delays, and administrative costs associated with rules of origin and impediments caused by nontariff barriers.[11] While data on preference use is hard to obtain, several surveys of trading firms suggest that preference use by exporting firms in Asian FTAs is not high in general (that is, the Indian experience is not very unusual). Thus, for a sample of 841 firms in East Asia, Kawai and Wignaraja (2011) have shown that only around 28% of exporting firms currently use PTA preferences.[12] Indeed, they found that 36% of reporting firms in South Korea and 14% in China cited “having had no substantial tariff preference or having had no actual benefits from such” as the major reason for not using the PTA preferential tariffs. Firms in the Philippines and Singapore attributed their low preference use to the countries’ overwhelming “export concentration in electronics,” which is characterized by “low MFN tariff rates.”

Finally, preference use is also limited by rules of origin, which are formulated in the context of PTA agreements to prevent trade deflection (that is, to ensure that goods that pass duty-free within the union are actually within-union goods and not produced outside). This is particularly important in the context of global production networks, which, through trade in intermediate goods, involve two or more countries in the production of a single final good. Often, rules of origin result in far less trade liberalization than is implied by the preferences negotiated within an agreement, as rules of origin may raise transaction costs for firms to a degree that makes use of FTA preferences uneconomical. This is especially likely when margins of preference are low, as described above. Furthermore, as the number of concluded agreements increases, different rules of origin in multiple overlapping PTAs can pose an additional burden on firms.

To summarize, India’s trade agreements have led to only modest trade liberalization.[13]

Global Value Chains and Trade Agreements

Increasing India’s exports will require greater willingness to liberalize trade. This is especially true considering the evolving patterns of international trade, specifically the evolution of global production networks, commonly referred to as global value chains, in neighboring countries in Asia, such as China, South Korea, and Japan, whose development trajectories India seeks to emulate. In GVCs, final goods are produced with inputs made in many different nations, and intermediate inputs may cross numerous international borders, with value being added at each stage before assembly into a final product. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) estimates that GVCs now account for about 70% of world trade.

As has often been observed, one difference between India’s trade pattern and those of many other countries in Asia is India’s low participation in GVCs, as demonstrated by a couple of measures. First, consider network products, defined by Athukorala (2012) as product groups that do not contain any finished product produced from start to end in a single country.[14] That is, network products are product groups in which different countries specialize in different parts of the production process. As Veeramani and Dhir (2019) have documented, the share of network products in India’s merchandise exports was less than 10%, while that of China, Japan, and South Korea was around 50%.[15] It is important to observe that the rapid success in increasing manufacturing exports in these countries accompanied a rapid increase in their exports of network products. Second, consider a related measure: the foreign content of domestic exports. OECD’s Inter-Country Input-Output tables indicate that between 2008 and 2020 the foreign content of India’s exports declined from 21.6% to 17.2%, while the OECD average rose from around 25% to 26.7%. Though, in the aggregate, India’s foreign content in exports is not very different from, say, China’s, there are important distinctions at the sectoral level. In India, the exporting industry with the greatest share of foreign intermediate inputs is coke and refined products, while in many neighboring countries in Asia, such as China, South Korea, Thailand, Vietnam, and Bangladesh, the comparable industries are ones that are important for employment growth: information and communications technology and electronics, and textiles and apparel.

Effective participation in GVCs will likely require India to make imports of intermediate inputs frictionless by eliminating tariffs and designing efficient rules of origin. Efficiency in imports could be achieved, in principle, through unilateral liberalization. However, for India’s exports to be frictionlessly imported by trade partners, its participation in regional trade agreements that facilitate such flows is crucial. Indeed, for much of the last decade, India was involved in negotiations over a megaregional agreement: the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). This was to be a free trade agreement between ASEAN nations and ASEAN’s FTA partners, and 16 countries were involved— Australia, Brunei, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Japan, Laos, South Korea, Malaysia, Myanmar, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam. These sixteen nations together constitute about a third of the world’s trade; their combined population is three billion, and their combined GDP is about US$20 trillion.

In 2019, however, after nearly a decade of negotiation, India announced its withdrawal from RCEP negotiations (retaining the option to join); the other countries have proceeded with the agreement. The lure of duty-free access to RCEP markets, along with the opportunity to frictionlessly integrate with Asia’s dynamic supply networks—and simultaneously provide domestic producers with a competitive boost—should have been tempting. Nevertheless, India chose to withdraw because of concerns about worsening trade balances (especially with China) and because of the potential for economic disruption. In particular, India feared that its domestic industry would be significantly challenged by competitive exports from RCEP countries, especially China. Further, India had an additional concern: if geopolitical relations worsened, would greater dependence on China bring major economic and strategic risks? Although one might hope that trade interdependence itself would support peace, policy decisions cannot rest on such hopes alone—especially if interdependence is asymmetric, as would be the case between India and China.[16] India’s border conflict with China has added geopolitical factors to an already-vexed economic calculation about RCEP while nourishing protectionist sentiment and enabling vested economic interests to find nationalistic cover.

India’s rejection of RCEP may prove economically costly.[17] Whether alternative arrangements that India is currently pursuing, such as FTAs with the United Kingdom and the EU, will represent offsetting opportunities is yet to be seen.

Policy Recommendations

The acceleration of India’s development trajectory will require India to exploit the scale and scope of global markets. In turn, this requires enhanced domestic productivity and improved market access. Given the stalled multilateral WTO liberalization process, PTAs offer an important opportunity for India to expand its access to global markets. However, for these agreements to have a meaningful impact, they need to be ambitious and bring liberalization that is substantially greater than what India has achieved through its previous trade deals. Effective participation in GVCs will require India to make imports of intermediate inputs frictionless by eliminating tariffs and designing efficient rules of origin. Of course, these reforms can be achieved through a unilateral approach or in the context of trade agreements. The urgency of such strategies to support the necessary structural transformation of India’s economy is clear. Whether India’s domestic political economy and geopolitical calculations permit such an approach is yet to be determined.

Concluding Remarks

This paper examined India’s experience with trade agreements over the past two decades. Trade outcomes under these agreements have been modest, with trade shares of India’s trade partners remaining steady and trade deficits not significantly increasing. The limited impact stems from the shallow reforms in trade policy, slow phase-in of liberalization, and complexity of rules of origin.

To improve trade competitiveness and access global markets, India should pursue unilateral liberalization of imports, especially intermediate inputs, and negotiate well-designed trade agreements. Increasing participation in global value chains will require India to eliminate tariffs and streamline rules of origin. Though domestic politics and geopolitical factors, particularly tensions with China, have impeded progress on agreements like RCEP, leveraging trade to support development remains crucial for India going forward. Undertaking strategic trade liberalization can thus help India utilize global markets to fuel its economic growth.

Notes

[1] Arvind Panagariya, India: The Emerging Giant (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008).

[2] Arvind Panagariya, Free Trade and Prosperity (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019); Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, FDI Stocks (database), accessed June 1, 2019, https://data.oecd.org/fdi/fdi-stocks.htm.

[3] Notwithstanding its emphasis on nondiscrimination in trade, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) permits the formation of preferential agreements (such as free-trade areas and customs unions) through Article XXIV, under the condition that such agreements liberalize “substantially all trade.”

[4] For a more detailed discussion of the trade-offs between unilateral, bilateral, and multilateral options in Indian trade policy, see Krishna (2022), on which the discussion in this section is based. Pravin Krishna, “India: Enhancing External Openness to Sustain Higher Growth,” in Grasping Greatness: Making India a Leading Power, ed. Ashley J. Tellis, Bibek Debroy, and C. Raja Mohan (Gurgaon, India: Penguin Random House India, 2023), 335–64.

[5] In contrast to Article XXIV, the Enabling Clause, introduced into the GATT in 1979, allows developing and least-developed members of the GATT to enter PTAs that do not require extensive liberalization. In practice, this has enabled dozens of agreements, involving only token liberalization, to be entered into by developing countries. It is important to note, as discussed more below, that India notified the WTO of most of India’s agreements under the Enabling Clause; the only exceptions are India’s agreements with Japan and Singapore.

[6] Many countries have individual agreements with India and are also part of a separate plurilateral agreement. Thus, Singapore has its own trade agreement with India and is also part of the India– ASEAN FTA. Goods can be freely imported or exported under whichever agreement gives Singapore more favorable treatment.

[7] For additional details concerning the modest impact of India’s FTAs, see Krishna (2021), on which the discussion in this section is based. Pravin Krishna, “India’s Free Trade Agreements,” Indian Public Policy Journal 2, no. 2 (March–April 2021): 1–12.

[8] Pravin Krishna, “Preferential Trade Agreements and the World Trade System: A Multilateralist View,” in Globalization in an Age of Crisis, eds. Robert Feenstra and Alan Taylor (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014).

[9] World Trade Organization, World Trade Report (Geneva: World Trade Organization, 2011).

[10] Baldwin and Seghezza examined correlations between MFN and PTA tariffs at the ten-digit level for twenty-three of the top exporting countries within the WTO for which data were available. Consistent with the preceding discussion, they found that MFN tariffs and PTA tariffs are complements, as the margin of preferences tends to be low or zero for products for which nations apply high tariffs. The implication is that we should not expect liberalization that is difficult at the multilateral level to proceed easily at the bilateral level. Richard E. Baldwin and Elena Seghezza, “Are Trade Blocs Building or Stumbling Blocs?,” Journal of Economic Integration 25, no. 2 (2010): 276–97.

[11] V. K. Saraswat, Prachi Priya, and Aniruddha Ghosh, A Note on Free Trade Agreements and Their Costs (New Delhi: NITI Aayog, 2017).

[12] Masahiro Kawai and Ganeshan Wignaraja, eds., Asia’s Free Trade Agreements: How Is Business Responding? (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 2011).

[13] A distinction is sometimes drawn between shallow agreements, involving only trade reform, and agreements such as those undertaken by the member countries of the EU, which involve deep integration, with convergence in institutional structures and other governance norms. As noted, India’s agreements have been shallow in the sense that not enough trade liberalization has been undertaken as a result.

[14] Specifically, Athukorala identifies seven product categories as network products: office machines and automatic data-processing machines (SITC 75), telecommunication and sound-recording equipment (SITC 76), electrical machinery (SITC 77), road vehicles (SITC 78), professional and scientific equipment (SITC 87), and photographic apparatus (SITC 88). Prema-chandra Athukorala, “Asian Trade Flows: Trends, Patterns, and Prospects,” Japan and the World Economy 24, no. 2 (2012): 150–62.

[15] C. Veeramani and Garima Dhir, “Dynamics and Determinants of Fragmentation Trade: Asian Countries in Comparative and Long-Term Perspective” (IGIDR Working Paper No. 2019-040, Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research, Mumbai Working Papers, Mumbai, India, 2019).

[16] China’s share in India’s trade (especially India’s imports) is quite significant, while India’s share in China’s trade is rather small. India also depends heavily on Chinese electronics exports and inputs for its pharmaceutical industry.

[17] Nearly five years have passed since the RCEP was signed. Although it would be illuminating to study the effects of RCEP on member countries, it would be premature to attempt an analysis now because of the disruptions to trade caused by the COVID pandemic. The liberalization committed to under the RCEP has a ten-year phase-in period, so, much of the agreed-to trade liberalization is yet to be undertaken.

Suggested Readings

Krishna, Pravin. “Preferential Trade Agreements and the World Trade System: A Multilateralist View.” In Globalization in an Age of Crisis, edited by Robert Feenstra and Alan Taylor, 131–64. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014.

Krishna, Pravin. “India’s Free Trade Agreements and the Future of India’s Trade Policy.” Indian Public Policy Journal 2, no. 2 (March–April 2021): 1–12.

Krishna, Pravin. “India: Enhancing External Openness to Sustain Higher Growth.” In Grasping Greatness: Making India a Leading Power, edited by Ashley J. Tellis, Bibek Debroy, and C. Raja Mohan, 335–64. Gurgaon, India: Penguin Random House India, 2023.