Each year until 2030, 8 million to 12 million young Indians will try to join the workforce, and most of them are expected to fail.[1] India’s ability to create jobs for them depends on solving two critical problems. First, a large portion of the workforce is employed in agriculture and the informal sector; second, employment growth has not kept pace with overall economic growth, often dubbed jobless growth. The situation is dire, moving beyond the economic realm to the social and political ones. The Union government, in its latest attempt to address this problem, has introduced incentives for each new employee hired and salary support for first-time workers in its latest budget.[2] We argue that the more fundamental problem is that India’s labor regulations impose too large a burden on firms too soon in their life cycle.

India grew at about 7% annually in the first two decades after liberalization in 1991. But during the same period (1991–2011), the share of manufacturing in GDP did not rise, unlike the growth of the Asian Tiger countries. Furthermore, 90% of jobs created in India were in the informal sector.[3] Most economists advocate a manufacturing- and export-driven growth model, similar to those that helped South Korea, China, Malaysia, Taiwan, and now Vietnam escape poverty.[4] For India to adopt this model, firms need to scale and become major sources of employment, value generation, and exports. Large-scale manufacturing operations like those in China are a rarity in India because 95% of India’s industrial units employ fewer than 10 workers. One of the main reasons Indian firms are reluctant to scale is prohibitively costly labor regulation.

India’s business regulatory framework consists of an overwhelming 1,536 laws, 69,233 compliance requirements, and 6,632 filings at the Union and state levels cumulatively,[5] which Manish Sabharwal has dubbed India’s “regulatory cholesterol.”[6] This regulatory cholesterol incentivizes firms to limit their size or operate in the informal sector to avoid compliance costs, thereby bifurcating the labor market into a small formal workforce and a large group left vulnerable in the informal sector.[7] India’s labor laws are among the most rigid, contributing to jobless growth and increasing informality.[8]

Surveying the literature on the impact of labor regulation, we find that India’s firm-level labor regulations punish businesses in two ways. First, the regulations are too onerous, preventing firms from remaining competitive. While some sectors and large-scale industries might be able to comply with this regulatory overload, most regulations are imposed on firms with as few as 10 employees, disincentivizing firm growth and large-scale employment. Second, labor-related regulations tend to micromanage factory operations through uncertain enforcement by a labor inspection system, further discouraging firms from expanding. India’s labor laws do too much, too soon in a firm’s life cycle.

We argue that to scale manufacturing across industries and foster job creation, India needs to revise its stringent labor regulations. This paper begins by describing the predominance of small-scale firms, indicating the extent of informality in India’s manufacturing sector, which is well established in the literature. It then shows that India’s labor law tries to do too much; instead of merely setting standards, the statutes micromanage workplaces, colors, fonts, uniforms, and more by requiring permissions for a host of workplace activities such as changing the tasks of a worker. It argues that the laws apply too soon in firms’ life cycle—namely, at low employee thresholds (typically as low as 10 workers). Both these aspects increase labor and compliance costs and discourage firms from scaling. Next, the paper offers recommendations for reforms to stop disincentivizing firms from scaling—including streamlining labor laws, raising employee thresholds, optimizing inspections, and avoiding excessive reliance on criminal penalties to ensure compliance.

We argue that to incentivize scale, ideally, the entire suite of labor regulations, especially statutes like the Factories Act, 1948 (now part of the Occupational Safety, Health, and Working Conditions Code, 2020), should be repealed and replaced with streamlined standards. However, such wholesale reform is often difficult to pull off politically, given the challenges of managing transitional gains traps, public protests, and a coalition government. As a second-best and immediate alternative, we recommend increasing the employee thresholds for the existing labor laws. Current thresholds vary between 10 and 100 workers. We suggest raising the thresholds to 1,000 workers for most labor regulations and 10,000 workers for regulations involving government in industrial disputes and factory closures. We also discuss the constitutional pathway for the reforms at the state level. These recommendations are followed by concluding remarks.

Too Small to Succeed

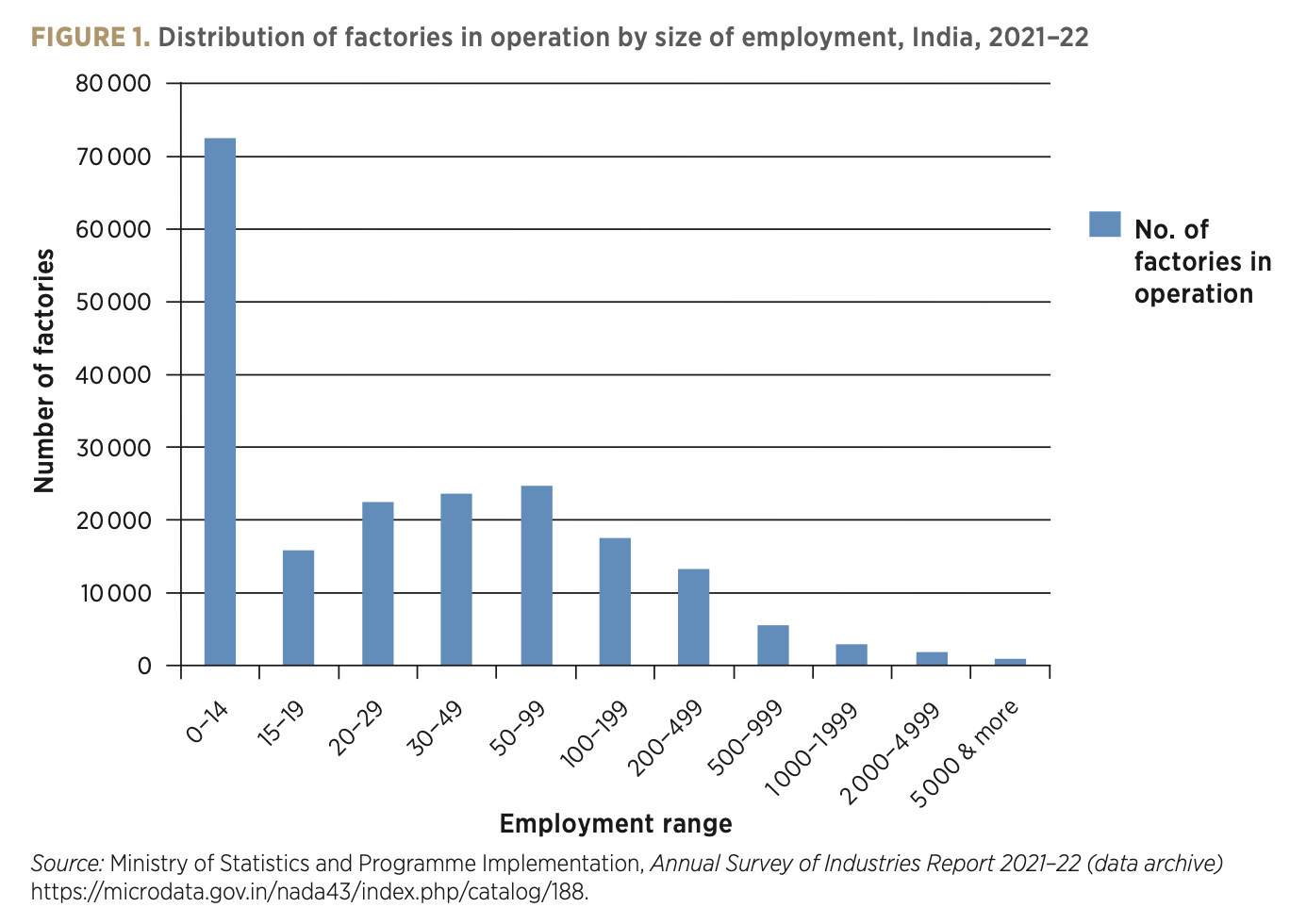

India is a large country with the potential to achieve large scale in nearly every sector, but it is characterized by a predominance of small firms.[9] Micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) make up 96% of India’s industrial units. Micro enterprises, employing fewer than 10 workers, constitute 99% of MSMEs. By definition, micro enterprises invest less than Rs 1 crore (Rs 10 million, or about US$120,000) and have turnover under Rs 5 crore (US$600,000). The remaining 1% of MSMEs employ 10 to 249 workers, invest up to Rs 20 crore, and have turnover reaching Rs 100 crore.[10] MSMEs generate 40% of industrial output and 42% of exports, with high potential for job creation. However, regulations hinder their ability to scale and prevent their integration into global value chains. Scaling these firms could enhance their competitiveness and profitability, but large-scale industrial enterprises remain rare (figure 1).

This phenomenon is often attributed to firms’ decision to stay small to avoid the costs of the regulatory state, including taxes, inspections, and compliance and corruption costs.[11] Firms willing to operate at scale face challenges in assembling factors of production because of the high regulatory and compliance costs.[12]

Small firms and cottage industries cannot benefit from economies of scale, which are crucial for manufacturers to reduce per-unit costs, offer lower prices, and gain a competitive edge.[13] As a result, they often struggle with limited access to capital, technology, and markets, which hampers their ability to lower production costs, invest in research and development, and adopt new technologies. These constraints make small firms more vulnerable to market shocks, seasonality, and global changes and limit their competitiveness and market share, leading to business failures or the need for extensive subsidies. The lack of large-scale manufacturing firms in India hampers the country’s economic growth and job creation.

Furthermore, this bottom-heavy industry structure leads to inefficiencies for producers and consumers,[14] thereby hindering the ability of firms to expand and engage in labor-intensive exports.[15] For these reasons, India’s firms are not competitive in export markets and are unable to replicate the miraculous growth achieved by firms in other Asian countries. Scaling enables greater specialization and efficiency, boosting a manufacturer’s productivity and market competitiveness. Data from the Annual Survey of Industries 2021–22 reveal a stark contrast between small and large firms.[16] Small firms (up to 50 workers) represent 66.95% of operational firms but account for only 8.97% of fixed capital, 12.59% of employment, 10.47% of output, and 6.35% of net value added. In comparison, the largest firms (5,000 or more employees) represent 0.38% of total firms yet use 21.86% of fixed capital, employ 9.53% of workers, produce 16.47% of output, and contribute 19.07% to net value added.

The difficulty in scaling affects not only Indian firms but also global companies seeking to establish new manufacturing hubs that can integrate into the global value chain. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, multinational companies were exploring the China Plus One strategy[17] to mitigate risks associated with overreliance on Chinese manufacturing. The urgency of mitigating these risks increased with operational disruptions that resulted from stringent COVID-19 measures and escalating trade tensions with the United States. Promising alternatives to China included Vietnam, Thailand, Bangladesh, Taiwan, and India. A 2012 McKinsey report predicted that diversification of production geographically combined with rising demand in India could boost India’s manufacturing sector to US$1 trillion by 2025 and create up to 90 million jobs.[18]

Many have noted India’s comparative advantage as a potential business hub.[19] Multilateral organizations are also optimistic about India’s future; for example, a 2021 World Economic Forum study stated that India could reshape supply chains and significantly contribute to the global manufacturing sector.[20]

Despite these forecasts and India’s significant advantages—being the world’s fifth-largest economy, ranking fifth in global manufacturing output, having the largest population and a sizable youth workforce, and having labor costs half of China’s—the country has not emerged as a primary destination for firms relocating from China.[21] According to a 2019 study by Nomura, between April 2018 and August 2019, while 56 companies moved their production from China, India received only 3 of these companies, while Vietnam received 26; Taiwan, 11; Thailand, 8; Mexico, 6; and Indonesia, 2.[22] A survey conducted by Gartner in early 2020 of 260 global supply chain leaders revealed that 33% had already moved or planned to shift their sourcing and manufacturing operations out of China by 2023.[23] Similarly, a 2023 report by Boston Consulting Group[24] found that over 90% of North American companies had relocated portions of their production and sourcing in the past five years, with many moving away from China. Both reports found that some of these operations were reshored to the United States, but Mexico, Vietnam, and India also saw gains. Yet India’s share of relocating companies has been small.

In developed countries, some firms are considered too big to fail. India faces the opposite problem: its firms are too small to succeed, largely because of burdensome regulation. The worst offender is labor regulation.

Labor Regulation: Too Much, Too Soon

The key to understanding labor regulation in India is that it amounts to too much and comes too soon in a firm’s life cycle. Labor-related statutes account for 30% of all firm regulation, 47% of all compliances, and 46% of filings required for business operations, imposing substantial costs on businesses at crucial growth junctures, usually at the 10-, 20-, and 50-employee thresholds.

The problem is not just how much regulation is not streamlined but what the government regulates. The Factories Act, 1948, mandates the provision of spittoons in convenient locations within factory premises, with state governments empowered to prescribe their type, number, and placement. Spitting anywhere except in these spittoons can result in fines up to Rs 5 (Section 20). The act also requires construction establishments to provide “soft” and “absorbent” toilet paper and specifies that latrine and urinal floors and walls must be finished with glazed tiles or similar materials up to a height of 90 centimeters (Section 19). Other regulations dictate the types of canteen utensils, light bulbs, and chairs as well as the water specifications and humidity control (respectively, Sections 46, 17, 47 18, and 15). Instead of setting basic standards for safety and hygiene, the regulations micromanage how firms keep their employees safe and punish firms—often through inspectors who demand bribes and foist criminal penalties—if that exact method is not followed.

Though the Factories Act is the worst offender, other labor laws exhibit micromanagement. The Shops and Establishments Acts, which vary by state, typically regulate door-swing directions and workroom temperatures and mandate that clocks be visibly displayed in all workrooms. The Plantations Labour Act, 1951, dictates the frequency of changing bed linens in worker accommodations (Section 24) and specifies the colors and intervals for painting such accommodations (Section 15). The Minimum Wages Act, 1948, specifies colors for official register paper and ink (Section 18) while the Payment of Wages Act, 1936, dictates wage-slip font sizes (Section 6). The Motor Transport Workers Act, 1961, regulates restroom dimensions and driver uniform colors (Section 13). The Maternity Benefit Act, 1961, specifies maximum distances between work areas and crèche facilities (Section 11). The Contract Labour (Regulation and Abolition) Act, 1970, regulates drinking water temperature (Section 18). The Building and Other Construction Workers Act, 1996, mandates shaded washing areas of certain sizes (Section 35). The Industrial Employment Act, 1946, requires bicycle racks for cycling workers (Section 13), and the Beedi and Cigar Workers Act, 1966, specifies minimum bench space in work areas (Section 13). The excesses of the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947, are well documented; in addition to its rules on hiring, firing, and firm closure, it requires firms to get the government’s permission before they reassign workers to different tasks. Violations of these laws can result in criminal penalties. The labor inspection system poses a tradeoff to firms: incurring high compliance costs or paying large bribes to avoid compliance.

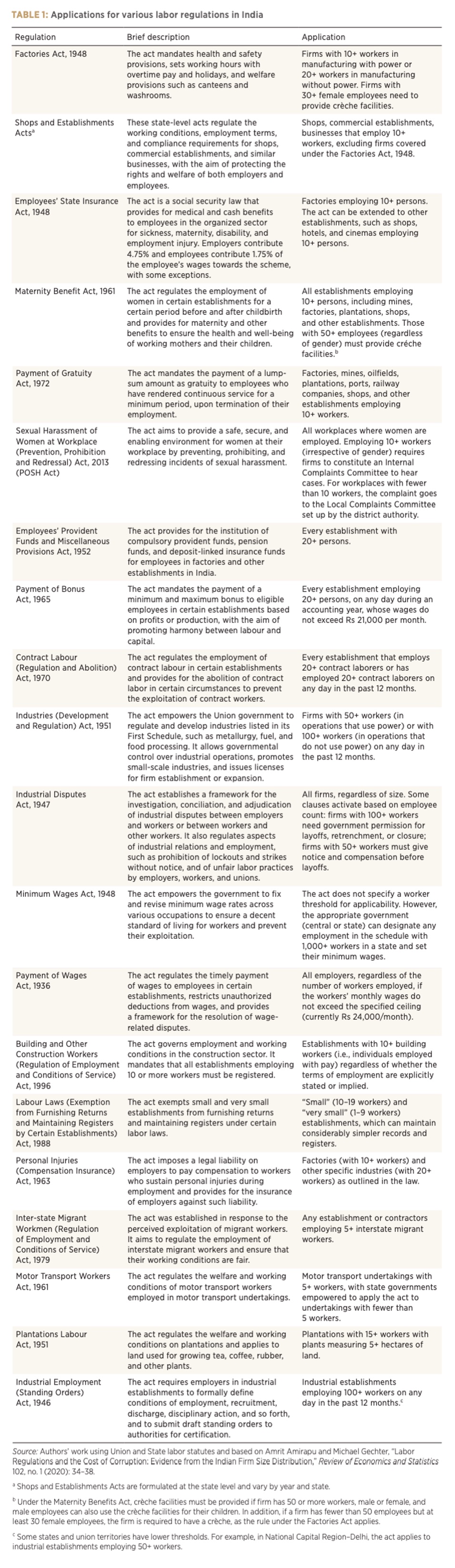

The second part of the problem is that this regulation largely kicks in too soon in firms’ life cycle. Most of it takes effect at the very low threshold of 10 workers (see table 1). The Factories Act, 1948, applies to firms with 10 or more workers using power (20 or more workers not using power). It mandates work hours, benefits, safety measures, paid time off, working conditions, and inspections. The regulatory excess does not end there: the Shops and Establishments Acts at the state level; the Employees’ State Insurance Act, 1948; the Maternity Benefit Act, 1961; the Payment of Gratuity Act, 1972; and the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace Act, 2013, all apply to firms with 10 or more workers. In addition, the Employees’ Provident Funds and Miscellaneous Provisions Act, 1952; the Payment of Bonus Act, 1965; and the Contract Labour (Regulation and Abolition) Act, 1970, apply to firms with 20 or more workers. If a firm with nine workers wishes to hire just one more worker, it must comply with almost the entire suite of regulation. This problem of very low thresholds for very costly regulation is underemphasized. Most of the focus of debate is usually on the Industries (Development and Regulation) Act, 1951, and the notorious Industrial Disputes Act, 1947, whose clauses largely apply to firms with 50 or more employees and 100 or more employees.

The standard philosophical argument from the left in favor of the suite of labor regulations is that employers typically hold more power in negotiating terms of employment because they control resources and employment opportunities. This type of thinking about policy solves for the old Marxist argument that workers, in competition and unable to coordinate, must accept poor and unsafe work conditions and low wages. Although the view is flawed, when we imagine this scenario in action, we typically think of a very large firm, with an individual or small group owning all the capital and employing thousands of workers. In such a scenario, those owning the capital control the resources, and they find it easy to coordinate and protect their interests. Meanwhile, hundreds or even thousands of workers are stuck in a prisoner’s dilemma: individually, each worker is better off accepting lower wages and worse conditions to secure employment, but collectively, this leads to a race to the bottom. Unions originally emerged to solve this problem by aligning individual and collective interests, as workers can jointly demand fair treatment without risking unemployment. However, even this scenario plays out only under very specific conditions outside of Charles Dickens novels: a large pool of low-skill, mostly substitutable labor, high concentration of capital, poor credit market, and costly technologies for coordination. It is no surprise that in India the demands for stricter regulation started in the textile mills in the late 19th century in Bombay, where about 87 mills collectively employed more than 125,000 workers.

India’s regulatory framework is misaligned with the reality of most work-places today. Firms with 10 workers are quite far removed from the capital-labor relationship and the power imbalances between employers and employees used to justify most of the existing labor regulation. They are akin to mom-and-pop shops, with a small number of workers with very specific skills. They tend to have higher cost per unit than larger firms and compete by providing highly local and/or bespoke goods and services. The coordination costs between laborers do not seem to be an issue, as the laborers typically work closely with each other in a relatively small space. And specifying the type of drinking water vessels, the height of urinals, and the kind of paint at a firm with just 11 workers seems bizarre. We can debate whether India’s labor law has proper philosophical moorings. But there is also the bigger and more urgent issue of the economic costs imposed by such regulation.

Impact: Stifling Scale

The biggest impact of the onerous labor regulation is that it disincentivizes firms from hiring more workers and prevents them from scaling. Low thresholds have various negative effects on India’s manufacturing growth, such as reductions in firm output, employment, investment, and productivity.[25]

India’s firm-level labor regulation punishes scale in two ways. First, it is too costly and does not allow firms to remain competitive. Very few sectors and firms can cope with this regulatory overload. As noted, most regulation is imposed on firms with as few as 10 employees, disincentivizing firms from growing large or employing many workers. They prefer to stay small, as it is the only way to survive and compete in the Indian market. A related aspect of staying small is remaining in the informal sector, again because it is too costly to follow all the regulations and formalize. And the informal sector cannot scale because the regulations disincentivize large, fixed investment and remaining small or violating onerous regulation preclude access to formal credit.

Firms face three types of regulatory costs. The first is the cost of compliance, which is nontrivial given the hyperspecific requirements regarding toilet paper, paint, water vessels, linen quality, urinal height, and font size. In addition to spending on these specific goods, a firm adding its 10th worker must hire additional workers just for regulatory compliance. Compliance regulations change with alarming frequency, further complicating operational planning. For example, from 2019 to 2021, the business regulatory landscape experienced more than 11,000 changes, averaging about 10 alterations daily.[26]

The second type of cost is imposed by increased interaction with labor inspectors extracting bribes (in addition to or in lieu of the compliance costs).[27] Inspectors in India wield significant discretion in enforcing administrative law.[28] For example, in some instances, the definition of what constitutes a day is at the discretion of the inspector, and it is commonly believed that “while grave violations are ignored, minor errors become a scope for harassment.”[29] This behavior has been referred to as “harassment bribery.”[30] Anecdotal evidence that inspectors exploit the complexity and sheer volume of paperwork to extract bribes is plentiful. Amirapu and Gechter (2020) look at a selection of citizen reports and observe that the size of the bribe paid is a direct linear function of the number of employees.[31] Clearly the license-permit raj of the old days was dismantled on many margins but is active and pernicious in the labor market.

Lahiri and Ali (2022) observe that while government authorities claim that inspections enforce compliance and deter corruption, private businesses often perceive the inspections themselves as corrupt, as inspectors use coercive measures that disrupt operations.[32] A 2017 survey of enterprises shows that firms report actual costs to be higher than prescribed fees because of the bribes and delays they face.[33] Throughout their life cycle, businesses are subject to a wide array of inspections by numerous regulatory authorities.

The inspection system in India increases costs but does not lead to additional safety for workers. This is partially because the laws are unrelated to real safety concerns and partially because the state does not have the capacity to enforce its own laws. For instance, the implementation of labor laws in India, such as the Minimum Wages Act, 1948, (and the Wage Code, 2020, not yet in force), is hindered by a dire shortage of labor inspectors. In 2012, data released by the labor bureau revealed that approximately 3,171 inspectors were responsible for overseeing an estimated 7.7 million establishments, equating to 2,428 establishments per inspector. With each inspector conducting two inspections per day, it would take five years for every establishment to be inspected once. India, despite being an International Labour Organization (ILO) signatory and having one of the most comprehensive labor protection frameworks in the world, falls short of the organization’s recommended ratio of labor inspectors to working population. The ILO prescribes a ratio of 1:40,000 for underdeveloped countries, whereas in India, the ratio stands at a staggering 1:120,000, highlighting the significant shortfall in the country’s labor inspection capacity. The combination of this shortfall and onerous regulation leads inspectors to be motivated to overlook violations and extort punitive bribes.[34]

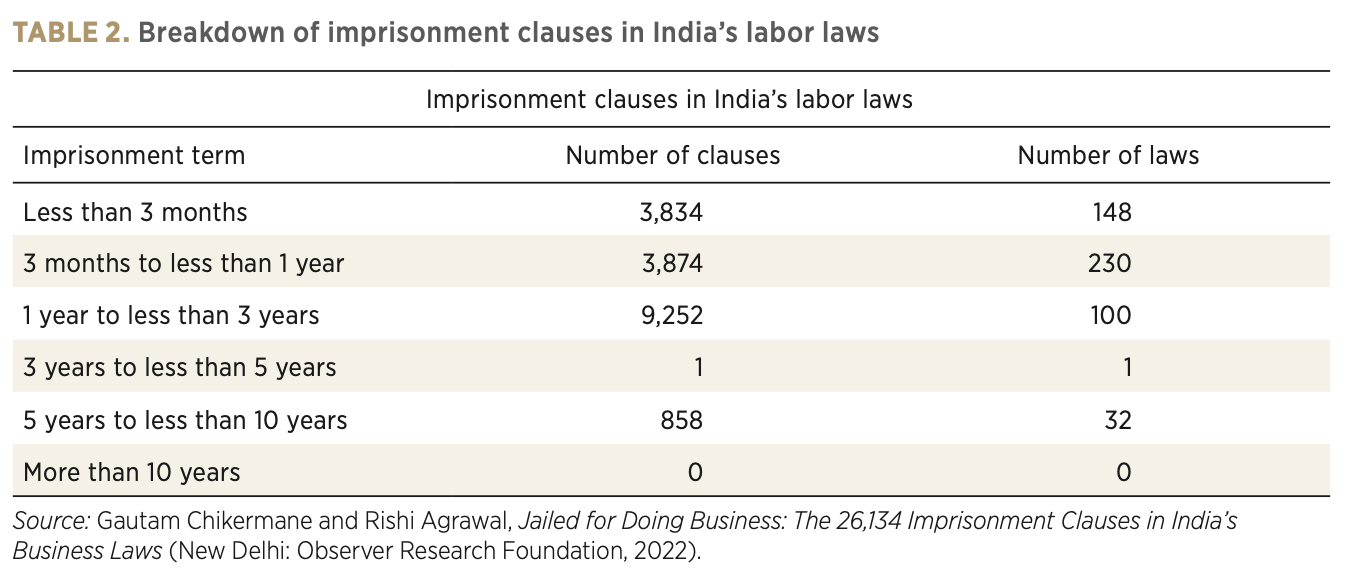

The third type of cost is the litigation cost. A 2022 report from the Observer Research Foundation, Jailed for Doing Business, sheds light on the daunting legal landscape that businesses must navigate. Navigating that landscape becomes increasingly complex and criminal penalties become more difficult to avoid as firms scale.[35] Five states have more than 1,000 imprisonment clauses in their business statutes: Gujarat, Punjab, Maharashtra, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu. Of the 1,536 acts that apply to businesses, more than half carry imprisonment clauses, and of the 69,233 compliances, over a third carry imprisonment clauses. Eighty percent of those clauses carry imprisonment terms of up to three years.[36] Labor-related regulations carry the highest number of criminal provisions, with an average of 50 such clauses per statute. For instance, not cleaning the floor of a workroom at least once a week can result in imprisonment of up to three months. Similarly, not maintaining tables, chairs, and benches in a canteen can lead to imprisonment of one to three years, and not displaying working hours prominently at a place of business can lead to imprisonment of five to ten years. The threat of criminal penalties for noncompliance adds a layer of risk that can deter business expansion and innovation and can incentivize firms to remain informal (table 2).

The punitive nature of some legal provisions for minor infractions, as opposed to intentional wrongdoing, raises concerns about proportionality and the rule of law. For instance, the penalty for delayed or inaccurate submission of a compliance report can be as severe as the penalty for sedition under the Indian Penal Code, 1860, equating procedural lapses with grave criminal offenses against the nation-state.[37] Moreover, the legal costs associated with navigating this complex regulatory environment can be substantial, deterring firms seeking to scale their operations. And uncertainty, especially owing to the inefficiency and endemic delays in the judicial system, hampers firms’ ability to scale.[38]

Hsieh and Klenow (2009) find that aggregate total factor productivity in India would be 40% to 60% higher if not for significant misallocation of resources across firms.[39] They also argue that India’s labor regulations may be responsible for this misallocation, as firms with 10 or more workers may face implicit costs associated with increased interaction with labor inspectors, who have the power to extract bribes and impose (or ease) administrative burdens on firms.

Chatterjee and Kanbur (2015), as well as Bardhan (2014), observe that firms deliberately choose to stay below the 10-worker threshold to sidestep labor regulations.[40] Chatterjee and Kanbur (2015) highlight that in the case of the Factories Act, 1948, the number of firms avoiding these regulations is more than double that of compliant firms.[41] Firms avoid regulations by staying small: noncompliant firms adjust their size to avoid regulation. Bardhan (2014) highlights that this pattern is particularly evident in the garment industry, where 92% of firms choose to employ fewer than eight workers to avoid falling under the purview of these labor regulations.[42]

The cost to firms owing to onerous regulation, low thresholds, and a pernicious inspection system is too high. Amirapu and Gechter (2020) study firm behavior in response to the 10-worker threshold and estimate the increase in unit labor costs associated with these regulations.[43] They find that the suite of labor regulations increases firms’ unit labor costs by 35% for firms across India (with variation between states). These costs include the explicit costs of complying with the regulations faced by firms with more than 10 workers and the implicit costs imposed by increased interaction with labor inspectors extracting bribes (in addition to or in lieu of the compliance costs).

Amirapu and Gechter (2020) show that at 10 workers, there is a downshift in the logged firm-size distribution, as reported in the 2005 economic census of firms in India.[44] This downshift may be a result of informality—that is, firms are a little larger but misreport the number of workers to avoid compliance, which also prevents them from further scaling. Alternatively, it could be that firms just above the threshold face higher unit labor costs than they would in the absence of the regulations and therefore employ fewer workers. The former factor would lead to informality in employment while the latter would lead to lower-than-optimal employment. The effect of these costs is to stifle firm scale.

Policy Recommendations

The very high costs imposed by India’s labor regulation on firms is well established, leading to a widespread consensus on the need for labor law reform. Youth unemployment is 45% and taking decades to educate youth and teach them skills is no longer realistic. They need employment right away in firms that provide room for growth and equitable participation.[45] Point estimates indicate that, on average, firms in labor-intensive industries and in flexible labor markets have total factor productivity residuals 25.4% higher than those registered for their counterparts in states with more stringent labor laws.[46] Besley and Burgess (2004), Aghion et al. (2008), and Dougherty (2009) observe that states with more flexible pro-employer regulations experience higher growth in firm size, employment, and wages vis-à-vis states with the more rigid pro-worker regulation.[47] Ahluwalia et al. (2018) find similar improvements within the apparel and textiles industries in regions with more flexible labor laws.[48] This contrast underscores the negative impact of stringent labor laws on firm scalability and suggests that relaxing regulations can foster a healthier business ecosystem.

Hasan, Mitra, and Ramaswamy (2007) study the interaction of trade liberalization with labor regulation.[49] They find that as tariffs and other trade barriers fell, the demand for labor became more sensitive to wage changes, particularly in states with more business-friendly labor regulations. As trade liberalized, Indian manufacturers faced more competition and gained access to imported inputs. This made it easier for firms to substitute between labor and other factors of production in response to price changes. It also made product markets more competitive, amplifying the effects of cost changes on output and employment. Thus, small changes in wages now led to bigger swings in employment than before. The effect was most pronounced in states that allowed firms more flexibility in hiring and firing workers. However, their findings also suggest that even modest reforms in labor law that decrease the cost of labor for the firm will increase hiring. Thus, Hasan, Mitra, and Ramaswamy (2007) show, in a way, that East Asian–style economic growth and employment growth led by export manufacturing might be possible in India if there were more flexible labor markets with further labor law reforms.

While the literature points to the need for labor reforms, there is less scholarship and less agreement about the details of such reforms. In recent years, efforts to simplify Indian labor laws led to the 2019–20 consolidation of 29 central labor statutes into four codes: the Code on Wages, the Code on Social Security, the Industrial Relations Code, and the Occupational Safety, Health, and Working Conditions Code. These codes aim to restructure regulations covering provisions from wages and social security to industrial relations and workplace safety. However, these changes have not yet been implemented, and the reform is merely a compilation of India’s vast labor regulation into a few codes. Much work remains to be done to further streamline labor laws and enact reforms that allow firms to scale.[50]

Moreover, on the issue of thresholds, the problem remains: The Codes of Safety, Social Security, and Occupational Safety, Health, and Working Conditions replicate the acts they comprise, applying to firms at 10 or 20 workers depending on the type of provision. If implemented in their current form, the new labor codes will not incentivize firms to hire more workers. The reason is that most of the new streamlined codes adopt the micromanagement of firms from the previous regulatory framework, which they continue to apply to businesses with as few as 10 workers, thereby maintaining the status quo. Only the Industrial Relations Code raises the threshold for requiring government permission for closures, layoffs, or retrenchments, from 100 to 300 workers, while also permitting the government to further raise the limit by notification.

As detailed in the previous sections, there are two problems related to labor law: too much and too soon. The current web of labor laws is too complex, and it is applied to very small firms at very low thresholds, with too many criminal penalties upon violation. The ideal policy is to repeal the existing suite of labor regulations, particularly statutes such as the Factories Act, 1948, and introduce simpler, streamlined protections using standard-form contracts and a minimal inspection regime, reserved only for health and safety provisions in a select few dangerous activities and for worker compensation, while leaving the rest of the details to contracts. Ideally, the state would create a sparse standard-form contract and let firms and employees negotiate the rest; such negotiation constantly takes place in small firms without high transaction costs.

Adopting a risk-based approach to inspections and prioritizing more frequent inspections of businesses with worse compliance records would reward companies with a strong history of compliance by reducing the frequency of their inspections, thereby encouraging adherence to regulations and efficient use of resources.[51] Alternatively, promoting the self-reporting process could enhance compliance and reduce the need for extensive inspections. Franco-Bedoya and Mani’s (2020) research indicates that compliance rates are significantly higher when firms self-report.[52] While these studies focus on environmental inspections, similar lessons may be applied to labor-related inspections.

Furthermore, criminal penalties in business-related laws must be used only in exceptional circumstances of worker safety and negligence, and labor regulation must eliminate criminalization of compliance procedures. Instead, civil penalties and fines may be used to ensure regulatory compliance. This change could motivate businesses to adhere to regulations while growing, as monetary penalties are often seen as less detrimental than jail time to a company’s reputation and operational continuity. And while standards can be set across all firms, provisions regulating precise workplace relationships should apply only to firms with more than 1,000 workers. However, there are various political economy constraints in this kind of wholesale reform of labor regulation, especially in a federal system.

This brings us to the too soon problem. It is well established that the thresholds are too low and, when increased, yield greater productivity and employment. The government’s own recent Economic Survey (2018–19) observed that even the marginally higher threshold—doubling it from 10 to 20 workers—in Rajasthan led to increases in both total output across the state and output per factory.[53] Imagine the impact at a 1,000-worker threshold! To support the expansion of smaller businesses, Indian states must be allowed to freely revise their labor laws and raise worker thresholds as deemed necessary.

If India chooses, for various political economy reasons, to continue with such burdensome labor regulations, at least it should not apply them to firms at such an early stage in their life cycle. We recommend increasing the threshold for all labor laws to 1,000 or more workers and specifically for industrial disputes and closures to 10,000 or more workers. This reform would have two clear benefits. First, firms that could be productive with, say, 350 workers would not be forced to remain informal because of the prohibitive cost of labor law compliance. Second, firms that were productive with, say, 22 workers would not remain small and hire only 9 workers to avoid the burden of compliance altogether, nor would they hire the additional 13 workers informally, through intermediaries, thereby creating instability and uncertainty for both the workers and the firms. Similarly, firms would not remain informal or only enter informal contracts through intermediaries (with no protection for labor) at 99 or more employees to avoid inspection under laws such as the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947.

Labor is a concurrent-list subject—that is, both the Union and state governments are allowed to legislate on labor matters. If central and state laws are incompatible, central laws prevail. For state laws to take precedence, amendments to the central law require the assent of the president. Increasing the thresholds for the application of statutes is not a point that makes state laws incompatible with central laws. However, when states have increased the thresholds, they have also made other amendments to the statute, thereby requiring presidential approval. For instance, in 2014, with the approval of the president, Rajasthan adjusted thresholds under the Factories Act, 1948, from 10 to 20 workers for factories using power and from 20 to 40 workers for those not using power.[54]

We recommend that every state in the Union of India increase the thresholds at which these laws apply to 1,000 or more workers and get presidential approval to do the same. This change will ensure that even without wholesale labor regulation reform by the Union government, which is stalled, states can pass reforms to help firms scale and hire more workers by working with the Union government to increase thresholds. The Union government can also increase the threshold for central laws such as the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947, to 10,000 or more workers for industrial disputes and closures. In addition to streamlining laws and increasing thresholds, optimizing inspection procedures, and minimizing criminal penalties could relieve firms of compliance burdens and allow them to grow by employing more workers.[55]

Concluding Remarks

India’s labor regulations have created a business environment that disincentivizes firms from scaling and hiring more workers. Over 95% of Indian firms remain small, with under 10 workers, in an economy that is struggling to create jobs. The complex web of labor laws, with their low employee thresholds and micromanagement of operations, imposes high compliance costs. These costs force firms to remain small or informal, hindering their ability to benefit from economies of scale, reach their productivity potential, and create much-needed job opportunities.[56] To address these challenges and unlock the potential of India’s manufacturing sector, we recommend repealing most of India’s labor regulation that micromanages firm inputs and then streamlining labor laws, increasing employee thresholds, revamping the inspections system to make it more efficient, and judiciously applying criminal penalties. In the absence of the wholesale repeal and reform, we recommend significantly increasing employee thresholds for most regulations to 1,000 workers (10,000 for industrial disputes and closures). These reforms can create a more conducive environment for the growth of large-scale firms, enabling them to enhance competitiveness and contribute to formal, stable employment opportunities.

Notes

[1] Economic Survey 2023–2024 estimates that India needs to create about 8 million nonfarm jobs per year until 2030, while a 2020 McKinsey report calculates that India needs to add about 12 million jobs a year to meet employment demands. Ministry of Finance, Economic Survey 2023–2024 (New Delhi: Government of India, 2024); Shirish Sankhe et al., India’s Turning Point: An Economic Agenda to Spur Growth and Jobs (McKinsey Global Institute, 2020).

[2] India’s 2024/25 budget introduces three job-boosting schemes to support employment. First-time workers can receive up to Rs 15,000 in salary support. The manufacturing sector gets Employees’ Provident Fund Organisation (EPFO)–linked incentives for both employers and employees. Additionally, all employers can claim Rs 3,000 monthly for new hires earning up to Rs 1 lakh (that is, Rs 100,000). These programs aim to benefit 29 million people, with a focus on youth and manufacturing jobs, aligning with the budget’s Next Generation Reforms theme. See the Budget Documents for 2024–2025, available on the Ministry of Finance’s website at https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/.

[3] Prachi Salve, “90% of Jobs Created over Two Decades Post-Liberalisation Were Informal,” India Spend, May 8, 2019. There is little difference in informality in 1991 vis-à-vis 2019; as the population grows, the informal sector will only keep growing. Indraneel Dasgupta and Saibal Kar, “The Labor Market in India Since the 1990s,” IZA World of Labor (2018): art. 425.

[4] Rana Hasan, Devashish Mitra, and K. V. Ramaswamy, “Trade Reforms, Labor Regulations, and Labor-Demand Elasticities: Empirical Evidence from India,” Review of Economics and Statistics 89 (2007): 466–81; Jayan J. Thomas, “India’s Labour Market During the 2000s: Surveying the Changes,” Economic and Political Weekly 47, no. 51 (2012), 39–51; Amrit Amirapu and Arvind Subramanian, “Manufacturing or Services? An Indian Illustration of a Development Dilemma” (Working Paper 408, Center for Global Development, June 2015); Arvind Panagariya, Free Trade and Prosperity (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019); Shoumitro Chatterjee and Arvind Subramanian, “India’s Export-Led Growth: Exemplar and Exception” (Working Paper 01, Ashoka Center for Economic Policy, October 2020); Centre for Sustainable Employment, State of Working India 2023: Social Identities and Labour Market Outcomes (Bengaluru, Karnataka: Azim Premji University, 2023); Amartya Lahiri and Devashish Mitra, “India’s Development Policy Challenge” (Mercatus Research Paper, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Arlington, VA, July 2024); Sudipta Ghosh, Amartya Lahiri, and Swapnika Rachapalli, “Productivity, Size and Market Competition” (mimeo, University of British Columbia, 2024).

[5] TeamLease Services, Compliance 3.0: Beyond Accidental Compliance (Pune, Maharashtra: TeamLease Services, 2016).

[6] Manish Sabharwal, “Life Skills Will Become More Important Than Technical Skills for Winning,” Economic Times, May 5, 2010.

[7] Timothy Besley and Robin Burgess, “Can Labor Regulation Hinder Economic Performance? Evidence from India,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 119, no. 1 (2004): 91–134; Kalpana Kochhar et al., “India’s Patterns of Development: What Happened, What Follows,” Journal of Monetary Economics 53, no. 5 (2006): 981–1019; Chang-Tai Hsieh and Peter Klenow, “Misallocation and Manufacturing TFP in China and India,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 124, no. 4 (2009); A. Srija and Shrinivas V. Shirke, “An Analysis of the Informal Labour Market in India, Economy Matters 19, no. 9 (2014): 40–46; Amrit Amirapu and Michael Gechter, “Labor Regulations and the Cost of Corruption: Evidence from the Indian Firm Size Distribution,” Review of Economics and Statistics 102, no. 1 (2020): 34–38; Amit Basole, “Structural Transformation and Employment Generation in India: Past Performance and the Way Forward,” Indian Journal of Labour Economics 65, no. 2 (2022): 295–320.

[8] T. C. A. Anant et al., “Labor Markets in India: Issues and Perspectives,” in Labor Markets in Asia: Issues and Perspectives, ed. J. Felipe and R. Hasan, 205–300 (London: Palgrave Macmillan for the Asian Development Bank, 2006); Aditya Bhattacharjea, “Labour Market Regulation and Industrial Performance in India: A Critical Review of the Empirical Evidence,” Indian Journal of Labour Economics 49, no. 2 (2006): 211–32; Alakh N. Sharma, “Flexibility, Employment and Labour Market Reforms in India,” Economic and Political Weekly 41, no. 21 (2006): 2078–85; Hasan, Mitra, and Ramaswamy, “Trade Reforms”; Aditya Bhattacharjea, “The Effects of Employment Protection Legislation on Indian Manufacturing,” Economic and Political Weekly 44, no. 22 (2009): 55–62; Urmila Chatterjee and Ravi Kanbur, “Non-compliance with India’s Factories Act: Magnitude and Patterns,” International Labour Review 154, no. 3 (2015): 393–412; Ritam Chaurey, “Labor Regulations and Contract Labor Use: Evidence from Indian Firms,” Journal of Development Economics 114 (2015): 224–32; Rafael La Porta and Andrei Shleifer, “Informality and Development,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 28, no. 3 (2014): 109–26.

[9] Dipak Mazumdar, “Small and Medium Enterprise Development in Equitable Growth and Poverty Alleviation,” in Reducing Poverty in Asia: Emerging Issues in Growth, Targeting, and Measurement, ed. Christopher M. Edmonds, 143–69 (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar for the Asian Development Bank, 2003); Dipak Mazumdar and Sandip Sarkar, Manufacturing Enterprise in Asia: Size Structure and Economic Growth (London: Routledge, 2013); Rana Hasan and Karl Robert Jandoc, “Labor Regulations and Firm Size Distribution in Indian Manufacturing,” in Reforms and Economic Transformation in India, ed. Jagdish Bhagwati and Arvind Panagariya, 15–48 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013); Pranab Bardhan, “The Labour Reform Myth,” Indian Express, August 23, 2014; Laura Alfaro and Anusha Chari, “Deregulation, Misallocation, and Size: Evidence from India,” Journal of Law and Economics 57, no. 4 (2014): 897–936; Santosh Mehrotra and Tuhinsubhra Giri, “The Size Structure of India’s Enterprises: Not Just the Middle Is Missing” (CSE Working Paper 25, Centre for Sustainable Employment, Asim Premji University, 2019).

[10] Data are from the Ministry of Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises, n.d., https://msme.gov.in/.

[11] Timothy Besley and John McLaren, “Taxes and Bribery: The Role of Wage Incentives,” Economic Journal 103, no. 416 (1993): 119–41; Dilip Mookherjee and I. P. L. Png, “Corruptible Law Enforcers: How Should They Be Compensated?” Economic Journal 105, no. 428 (1995): 145–59; TeamLease Services, India Labour Report 2006: A Ranking of Indian States by Their Labour Ecosystem (Pune, Maharashtra: TeamLease Services, 2006); Lant Pritchett, “Is India a Flailing State? Detours on the Four Lane Highway to Modernization” (HKS Faculty Research Working Paper 09-013, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, 2009); Amrit Amirapu and Michael Gechter, “Labor Regulations and the Cost of Corruption,” 34–48.

[12] Arvind Panagariya, India: The Emerging Giant (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008); Subhash C. Ray, “Are Indian Firms Too Small? A Nonparametric Analysis of Cost Efficiency and the Optimal Organization of the Indian Manufacturing Industry,” Indian Economic Review 44, no. 1 (2009): 49–67; James Tybout, “The Missing Middle, Revisited” (working paper, Pennsylvania State University, 2014); NITI Aayog and IDFC Institute, Ease of Doing Business: An Enterprise Survey of Indian States (New Delhi: NITI Aayog, 2017).

[13] Poonam Gupta, Rana Hasan, and Utsav Kumar, “Big Reforms but Small Payoffs: Explaining the Weak Record of Growth in Indian Manufacturing” (MPRA Paper 13496, Munich Personal RePEc Archive, February 18, 2009); Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Skills Development and Training in SMEs (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2013); Dipankar Gupta, “Think ‘Big’: Strategizing Post-coronial Revival in India,” Indian Journal of Labour Economics 63, suppl. 1 (2020): 145–50; Andrea Ciani et al., Making It Big: Why Developing Countries Need More Large Firms (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2020).

[14] Hasan and Jandoc, “Labor Regulations.”

[15] Bibek Debroy, “Issues in Labour Law Reform,” in Reforming the Labour Market, ed. Bibek Debroy and P. D. Kaushik, 37–76 (New Delhi: Academic Foundation, 2005).

[16] Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Annual Survey of Industries 2021–22 (data archive), https://microdata.gov.in/nada43/index.php/catalog/188.

[17] The China Plus One strategy refers to the business approach of diversifying manufacturing and supply chains by establishing operations in countries outside of China, thereby reducing reliance on a single nation.

[18] Rajat Dhawan, Gautam Swaroop, and Adil Zainulbhai, “Fulfilling the Promise of India’s Manufacturing Sector,” McKinsey, March 1, 2012.

[19] Amita Batra and Zeba Khan, “Revealed Comparative Advantage: An Analysis for India and China” (Working Paper 168, Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations, New Delhi, 2005); T. N. Srinivasan, “China, India and the World Economy,” Economic and Political Weekly 41, no. 34 (2006): 3716–27; Gurcharan Das, “The India Model,” Foreign Affairs 85, no. 5 (2006): 2–16.

[20] World Economic Forum, “India’s Opportunity to Become a Global Manufacturing Hub,” press release, August 2, 2021.

[21] MES, “China vs. India. A Sourcing Experience” (white paper, MES, October 2015).

[22] Abhinandan Mishra, “Firms Leaving China, but Not Moving to India,” Sunday Guardian, October 12, 2019.

[23] Gartner, “Gartner Survey Reveals 33% of Supply Chain Leaders Moved Business out of China or Plan to by 2023,” press release, June 24, 2020.

[24] Boston Consulting Group, “More Than 90% of North American Companies Have Relocated Production and Sourcing over the Past Five Years,” press release, September 21, 2023.

[25] Ray, “Are Indian Firms Too Small?”; Besley and Burgess, “Can Labor Regulation Hinder Economic Performance?”; Panagariya, India; Hsieh and Klenow, “Misallocation and Manufacturing TFP”; Tybout, “Missing Middle”; NITI Aayog and IDFC Institute, Ease of Doing Business.

[26] Gautam Chikermane and Rishi Agrawal, Jailed for Doing Business: The 26,134 Imprisonment Clauses in India’s Business Laws (New Delhi: Observer Research Foundation, 2022).

[27] Research also shows that larger firms are more likely to be inspected than small firms, further incentivizing firms to stay small. Rita Almeida and Lucas Ronconi, “Labor Inspections in the Developing World: Stylized Facts from the Enterprise Survey,” Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society 55, no. 3 (2016): 468–89.

[28] Bibek Debroy, “India’s Segmented Labour Markets, Inter-state Differences, and the Scope for Labour Reforms,” in Economic Freedom of the States of India 2012, ed. Bibek Debroy, Laveesh Bhandari, Swaminathan S. Anklesaria Aiyar, and Ashok Gulati, 75–82 (Academic Foundation, 2013).

[29] TeamLease Services, India Labour Report 2006.

[30] Kaushik Basu, “Why, for a Class of Bribes, the Act of Giving a Bribe Should Be Treated as Legal” (MPRA Working Paper 50335, Munich Personal RePEc Archive, March 2011).

[31] Amirapu and Gechter, “Labor Regulations.”

[32] Bidisha Lahiri and Haider Ali, “Inspections, Informal Payments and Tax Payments by Firms,” Finance Research Letters 46, Part A (2022): art. 102311.

[33] NITI Aayog and IDFC Institute, Ease of Doing Business.

[34] Shruti Rajagopalan and Alex Tabarrok, “Simple Rules for the Developing World,” European Journal of Law and Economics 52, no. 2 (2021): 341–62.

[35] Chikermane and Agrawal, Jailed for Doing Business.

[36] Chikermane and Agrawal, Jailed for Doing Business.

[37] Chikermane and Agrawal, Jailed for Doing Business.

[38] Matthieu Chemin, “Does the Quality of the Judiciary Shape Economic Activity? Evidence from India” (working paper, London School of Economics, November 8, 2004); Pavel Chakraborty, “Judicial Quality and Regional Firm Performance: The Case of Indian States,” Journal of Comparative Economics 44, no. 4 (2016): 902–18.

[39] Hsieh and Klenow, “Misallocation and Manufacturing TFP.”

[40] Chatterjee and Ravi Kanbur, “Non-compliance with India’s Factories Act”; Bardhan, “Labour Reform Myth.”

[41] Chatterjee and Kanbur, “Non-compliance with India’s Factories Act.”

[42] Bardhan, “Labour Reform Myth.”

[43] Amirapu and Gechter, “Labor Regulations.”

[44] Amirapu and Gechter, “Labor Regulations.”

[45] Pravin Visaria, “Unemployment among Youth in India: Level, Nature and Policy Implications” (Employment and Training Paper 36, International Labour Office, Geneva, 1998); S. Mahendra Dev and Motkuri Venkatanarayana, “Youth Employment and Unemployment in India” (Mumbai Working Paper 2011-009, Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research, Mumbai, 2011); Arup Mitra and Sher Verick, “Youth Employment and Unemployment: An Indian Perspective” (ILO Asia-Pacific Working Paper 994806863402676, International Labour Organization, 2013); Santosh Mehrotra, “The Indian Labour Market: A Fallacy, Two Looming Crises and a Tragedy” (SWI Background Paper, Centre for Sustainable Employment, Azim Premji University, 2018); Santosh Mehrotra and Jajati Parida, “India’s Employment Crisis: Rising Education Levels and Falling Non-agricultural Job Growth” (CSE Working Paper 23, Centre for Sustainable Employment, Azim Premji University, 2019).

[46] Sean Dougherty, Veronica Frisancho, and Kala Krishna, “State-Level Labor Reform and Firm-Level Productivity in India,” India Policy Forum 10, no. 1 (2014): 1–56.

[47] Besley and Burgess, “Can Labor Regulation Hinder Economic Performance?”; Philippe Aghion et al., “The Unequal Effects of Liberalization: Evidence from Dismantling the License Raj in India,” American Economic Review 98, no. 4 (2008): 1397–412; Sean M. Dougherty, “Labour Regulation and Employment Dynamics at the State Level in India,” Review of Market Integration 1, no. 3 (2009): 295–337. While there have been methodological debates surrounding these studies, there is broad consensus in the literature on the need for labor law reform to enhance India’s economic performance and facilitate firm growth. Bhattacharjea, “Labour Market Regulation and Industrial Performance in India”; Jaivir Singh, “Frustrating or Perhaps Supportive of Economic Activity? A Law and Economics Take on Labour Law in India,” GNLU Journal of Law and Economics 1, no. 1 (2018): 123-38.

[48] Rahul Ahluwalia et al., “The Impact of Labor Regulations on Jobs and Wages in India: Evidence from a Natural Experiment” (Working Paper 2018-02, Deepak and Neera Raj Center on Indian Economic Policies, Columbia University, 2018).

[49] Hasan, Mitra, and Ramaswamy, “Trade Reforms.”

[50] Shruti Rajagopalan, “The 1991 Reforms and the Quest for Economic Freedom in India,” Capitalism and Society 15, no. 1 (2021): 1–26.

[51] Esther Duflo et al., “Truth-Telling by Third-Party Auditors and the Response of Polluting Firms: Experimental Evidence from India,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 128, no. 4 (2013): 1499–545; Esther Duflo et al., “The Value of Regulatory Discretion: Estimates from Environmental Inspections in India,” Econometrica 86, no. 6 (2018): 2123–60.

[52] Sebastian Franco-Bedoya and Muthukumara Mani, “The Drivers of Firms’ Compliance to Environmental Regulations: The Case of India” (Policy Research Working Paper 9468, World Bank, Washington, DC, 2020).

[53] Ministry of Finance, Economic Survey 2018–2019 (New Delhi: Government of India, 2019).

[54] PRS India, “Overview of Labour Law Reforms,” n.d., https://prsindia.org/billtrack/ overview-of-labour-law-reforms.

[55] Juan C. Botero et al., “The Regulation of Labor,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 119, no. 4 (2004): 1339–82; Chandan Sharma and Arup Mitra, “Corruption, Governance and Firm Performance: Evidence from Indian Enterprises,” Journal of Policy Modeling 37, no. 5 (2015): 835–51.

[56] Kapoor and Krishnapriya (2017) suggest that the presence of contract workers does not necessarily negatively impact firm productivity, although in certain instances their productivity levels can be inferior compared to those of regular employees. Radhicka Kapoor and P. P. Krishnapriya, “Informality in the Formal Sector: Evidence from Indian Manufacturing” (IGC Working Paper F-35316-INC-1, International Growth Centre, 2017).